BREAKING THE ICE: IS FEDNAV TURNING EMISSIONS INTO OPPORTUNITY FOR THE SHIPPING INDUSTRY?

How Canadian dry-bulk ocean shipper Fednav is charting new waters and exploring an opportunity for the shipping industry

On board the MV Nunavik in September 2014, some of the crew stripped down for the “Arctic Ice Bucket Challenge.” Dousing themselves for a good cause, they floated amidst the results of environmental damage linked by some, in part, to their industry.

Environmental Challenge

As is well documented, climate change – or increases in temperature due to “radiative forcing” – is causing reductions in ice fields. [1] Polar melting (along with sea temperature increases), in turn, has caused rising sea levels. Estimates suggest increases up to 2 meters (6.6 feet) by 2100.[2] The impact of sea level changes could be wide-ranging. Low-lying land submersion, for example, could relocate 470 to 670 million people around the world. In addition to damaging coastal dwellings, broader economies would suffer from the disruption of coastal trade and agriculture.[3]

Impact to Shipping Business Models

The shipping industry lies at the center of these challenges. As both a significant emitter and an industry sensitive to climate change’s effects, it offers a useful gateway into how businesses approach prevention and response efforts.

According to Transport and Environment (an organization dedicated to research and tracking the impact of transportation on the environment), international shipping accounts for approximately 3% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. [4] Emissions have increased approximately 70% since 1990, largely due to i) the expansion of global freight trade and ii) growing containerization penetration. [5] Without adjustments to its business practices, experts have suggested that the industry could account for as much as 10% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050.[6]

In July 2011, the industry took its first binding steps towards increasing efficiency. The International Maritime Organization – the industry’s key international regulatory body (part of the United Nations) – approved the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) and the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP).[7] The resolution set new standards for new and current vessel emissions, using a key industry metric: grams of CO2 per tonne mile. Last week, the IMO announced an additional measure to bolster EEDI and SEEMP: a consumption data collection system for ships carrying over 5,000 gross tonnage of cargo.[8] Speaking on October 28, 2016, IMO Secretary General Kitack Lim mentioned the system will continue “proving to the world the IMO continues to lead in delivering on the reduction of greenhouse emissions from international shipping.”[9]

In addition to prevention efforts through ship efficiency, climate change is expected to impact the sea shipping business model in several ways. Rising sea levels may extend deep water areas, accommodating larger ships in more channels. Inland, higher levels could lower clearance levels under bridges. Coastal ports could also experience damage.[10]

FedNav’s Approach

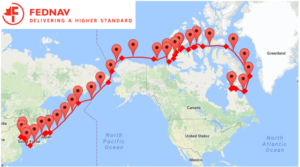

In addition to these challenges and efficiency efforts, Fednav, Canada’s largest ocean-going dry-bulk shipping group, sees opportunity in this changing landscape. In 2014, the group made headlines when adding a new ice-breaker ship to its fleet. Capable of moving continuously at 3 knots in 1.5 meters of ice, it was the most powerful non-nuclear icebreaking bulk carrier in the world. Upon completion, Fednav CEO Paul Pathy announced “Fednav is particularly proud of the arrival of this new ship. It represents Fednav’s commitment to mining development in the Arctic, as well as our dedication to technological development and energy efficiency.”[11] In October 2014, the MV Nunavik completed a solo trip through the Northwest Passage (NWP), the stretch of the Arctic Ocean that connects the northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. [12] Its ice-breaking ship, the MV Nunavik, hauled 23,000 tons of nickel ore from Canada’s Deception Bay to the Chinese Port of Bayuquan – the first major commercial operation of its kind.[13] The trip was completed 40% faster than the traditional route through the Panama Canal. [14] Moreover, the route reduces GHG emissions by 1,300 metric tons.[15]

Looking ahead, Fednav’s journey has raised important questions about the role of polar melting in shipping. It remains, however, still a young debate. In a paper published in September 2015, researchers from York University in Canada cautioned that, given ice conditions from 2011-2015 (mean ice of thickness of 3 meters for the full year), “shipping through the NWP should not be taken lightly.” [16] They also cited a lack of data as a key problem for research. Others, however, might point to past under-predictions of sea-ice decline (see 2009 IPCC report) as evidence that FedNav may be leading a critical development sooner than many think.[17]

What’s your take?

Word Count: 758

[1] Rebecca Henderson, Sophus Reinert, Polina Dekhtyar, and Amram Migdal, “Climate Change in 2016,” HBS No. N2-317-302 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), P. 1.

[2] Rebecca Henderson, Sophus Reinert, Polina Dekhtyar, and Amram Migdal, “Climate Change in 2016,” HBS No. N2-317-302 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), P. 2.

[3] Rebecca Henderson, Sophus Reinert, Polina Dekhtyar, and Amram Migdal, “Climate Change in 2016,” HBS No. N2-317-302 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), P. 3.

[4] Transport and Environment, “Smarter Steaming Ahead,” https://www.transportenvironment.org/publications/smarter-steaming-ahead, accessed November 2016.

[5] Transport and Environment, “Shipping and Climate Change,” https://www.transportenvironment.org/what-we-do/shipping/shipping-and-climate-change, accessed November 2016.

[6] Transport and Environment, “Shipping and Climate Change,” https://www.transportenvironment.org/what-we-do/shipping/shipping-and-climate-change, accessed November 2016.

[7] International Maritime Organization, “Technical and Operational Measures,” http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/PollutionPrevention/AirPollution/Pages/Technical-and-Operational-Measures.aspx, accessed November 2016.

[8] “New requirements for international shipping as UN body continues to address greenhouse gas emissions,” press release, October 28, 2016, on IMO website, http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/28-MEPC-data-collection–.aspx, accessed November 2016.

[9] “New requirements for international shipping as UN body continues to address greenhouse gas emissions,” press release, October 28, 2016, on IMO website, http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/28-MEPC-data-collection–.aspx, accessed November 2016.

[10] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Climate Impacts on Transportation,” https://www.epa.gov/climate-impacts/climate-impacts-transportation#ref1, accessed November 2016.

[11] “Fednav Brings New Icebreaker to the Canadian Arctic,” press release, on Fednav website, http://www.fednav.com/en/media/fednav-brings-new-icebreaker-canadian-arctic, accessed November 2016.

[12] “Cargo Ship Is First to Solo the Northwest Passage,” October 2, 2014, Seeker News, http://www.seeker.com/cargo-ship-is-first-to-solo-the-northwest-passage-1769130069.html, accessed November 2016.

[13] “Cargo Ship Is First to Solo the Northwest Passage,” October 2, 2014, Seeker News, http://www.seeker.com/cargo-ship-is-first-to-solo-the-northwest-passage-1769130069.html, accessed November 2016.

[14] “Nunavik’s Log Book,” last updated October 17, 2014, http://www.fednav.com/en/voyage-nunavik, accessed November 2016.

[15] “Cargo Ship Is First to Solo the Northwest Passage,” October 2, 2014, Seeker News, http://www.seeker.com/cargo-ship-is-first-to-solo-the-northwest-passage-1769130069.html, accessed November 2016.

[16] Haas, Christian. and Howell, Stephen, “Ice thickness in the Northwest Passage,” Geophysical Research Letters (September 2015), http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2015GL065704/full 42, 7673–7680, accessed November 3, 2016.

[17] Rebecca Henderson, Sophus Reinert, Polina Dekhtyar, and Amram Migdal, “Climate Change in 2016,” HBS No. N2-317-302 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), P. 3

Interesting article; I think it’s the only company I’ve read about thus far in which the business actually benefits from the effects of climate change. Whereas climate change is limiting other industries’ raw material supply, Arctic shipping opportunities are actually increasing because of the polar ice cap is melting. I wonder how FedNav will continue to balance its need to reduce GHG emissions while taking advantage of a longer shipping season. Should the company even consider these new routes, and will it receive backlash from environmentalists if it does?

This seems like it could be a huge opportunity for the shipping industry. I hope that it economically makes sense, given that an ice breaking ship is likely more expensive to build and to operate. I wonder if shipping companies could scale this and actually make a dent in the total carbon output of the fleet. I’m not sure how much cargo would benefit from this, but it seems like it would be a lot of bulk materials and maybe even some north US or northern Europe cargo.

They could potentially scale this operating model by having multiple standard cargo ships caravan behind an ice breaking one. In addition, they could just use this boat for what it is good at and just do the arctic journey, dropping off it’s cargo in Alaska and then having a standard container ship continuing the journey to China.