Crowdsourcing the Future with Hyperloop

Can one of today’s most hyped technologies be solved by crowdsourcing? Many challenges lie ahead.

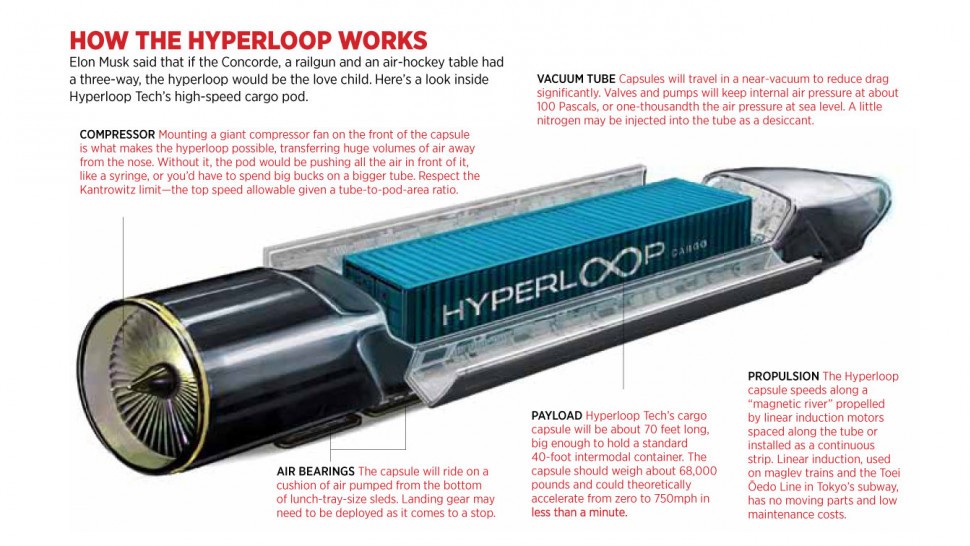

You’ve probably heard of the Hyperloop. It’s one of those words that often comes up in conversations with other exciting-sounding words like “SpaceX” and “Elon” and “the Future” (with a capital F). Zipping from LA to SF in 30 minutes through a vacuum tube? It may be closer to reality than you think.

The Hyperloop technology was introduced by Elon Musk in a 2013 white paper, and shortly thereafter, two companies were established to embark on the challenging work of transforming that idea into reality. One of the companies, called Hyperloop One, is a traditional VC-backed startup; the other, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT), is a crowdsourced endeavor that relies on the ideas and work of part-time collaborators. Which of these two equally creatively-named companies will be first to market to realize the Hyperloop dream?

The beginnings of making Hyperloop a reality

HTT was born in 2013 out of JumpStartFund, a crowdsourced online incubator for early stage tech companies. As a collaboration platform, JumpStartFund believes that its engaged community can offer validation around an idea in the early stages of a company’s life, thus increasing the probability of finding product market fit. From its early days, HTT boasted an impressive slate of collaborators, including Ansys, a computer-aided engineering and simulation firm, which had already conducted an independent study on the feasibility of Hyperloop, GloCal Network Corporation, a materials science company, and the UCLA Architecture and Urban Design Department. Since 2013, a laundry list of global companies have since joined to offer in-kind services, including composites manufacturers, design and engineering firms, marketing firms and AR/VR companies.

What makes HTT truly interesting, beyond its lofty technological goals, is its crowdsourced structure. HTT has no full-time employees. Rather, it has crowdsourced work from over 600 individuals, including “more than 200 professionals from 44 companies in 38 countries”, who work on the Hyperloop project in exchange for stock options (even the CEO, Dirk Ahlborn, only has stock options as compensation ). These individuals work full-time at established organizations like Boeing, Airbus and NASA and dedicate weeknights and weekends to working on HTT; the company simply asks that they spend at least 10 hours a week on HTT, but there is no real enforcing mechanism.

). These individuals work full-time at established organizations like Boeing, Airbus and NASA and dedicate weeknights and weekends to working on HTT; the company simply asks that they spend at least 10 hours a week on HTT, but there is no real enforcing mechanism.

So far, investors, transportation companies and municipal governments seem to be buying it. HTT claims to have raised over $108mm in investment, though only $32mm is in cash investments from VCs and the remaining non-cash portion is attributed to man-hours, services rendered, land rights usage and future in-kind investments (a rather unique (perhaps, loose) definition of investments). The website states that they’ve signed agreements to build in California (Quay Valley), Slovakia, Abu Dhabi and Toulouse, with the expectation that they will test a demo train in 2017. HTT has further demonstrated its market validation through a collaboration with Deutsche Bahn to build an “Innovation Train”, a conventional train that will use innovative technologies developed by HTT.

Does a crowd maketh a company?

W hile it has certainly shown thus far that it is adept at securing partnerships and signing on early market testers, HTT calls into question the fundamental question of the benefits of crowdsourcing for this particular problem. HTT’s leadership believes that crowdsourcing allows them to gain access to the best global talent at a lower cost. This crowdsourced nature allows the best ideas to surface, an important process for a project as visionary and untested as this one. The stock option structure ostensibly incentivizes collaborators to care more deeply about the success of the company, and the collaborative nature socializes the vision amongst the community.

hile it has certainly shown thus far that it is adept at securing partnerships and signing on early market testers, HTT calls into question the fundamental question of the benefits of crowdsourcing for this particular problem. HTT’s leadership believes that crowdsourcing allows them to gain access to the best global talent at a lower cost. This crowdsourced nature allows the best ideas to surface, an important process for a project as visionary and untested as this one. The stock option structure ostensibly incentivizes collaborators to care more deeply about the success of the company, and the collaborative nature socializes the vision amongst the community.

There are some technical, project-oriented crowdsourcing success stories that HTT can point to. For example, rLoop, an open source group of 140 individuals formed on Reddit, was the only non-student group to reach the final stage of SpaceX’s Hyperloop Pod Competition in 2016. rLoop individuals – hailing from the likes of NASA, Tesla and GE – used Google Docs, Slack and Trello to communicate and collaborate for the competition and never met in person.

Despite the espoused virtues of crowdsourcing, many challenges lie ahead. From my perspective, some of the biggest challenges are as follows:

- Complexity of the project: Building the Hyperloop is a herculean endeavor. How does HTT ensure that there are enough people working on each piece of the project? How do they incentivize people to work on the non-sexy parts? There must be strong communication amongst the collaborators or the company will fall into the trap of wasted time and effort.

- Coordination: Is more ideas always better? Who makes the final call on key decisions? Thomas Lambot, the engineering lead of rLoop (the crowdsourced group mentioned above), said “There are a great number of people who join excitingly, start doing great work and take on responsibilities. Within a week they say, ‘I can’t do that anymore, this is insane’ and just disappear. That happens all the time—people joining, helping, and disappearing. It’s like herding cats trying to get people focused over the internet. But I can’t take them by the shirt and say ‘focus’ or threaten to fire them either.”

- Ideas vs. execution: Crowdsourcing may work well for idea generation, by allowing collaborators to bounce ideas off of each other and by getting impressive volume and diversity of ideas, but does it work for execution? Execution requires a big picture strategy and coordinated efforts; how do independent contributors execute in sync with each other? With the right timing and sequencing of steps?

- Liability: If this fails, who’s liable?

- Misalignment: Will collaborators be aligned on the business model? Some may care about monetization more or less than others, which may affect the technological design process of the project. How do different perspectives on value capture affect the technology itself?

- Timing concerns: If a city government asks for a strict timeline and HTT has to rush to meet it, can it do so when they don’t “own” any of their contributors’ time? HTT essentially has unsecured resources that they can’t reliably rally when needed.

- Talent: Does the best talent out there have free time to even do something like this? Is HTT actually accessing the best talent?

- Sustained engagement: With inevitable delays in timing (for example, the CEO had originally stated that he wanted to IPO in 2016), how does HTT keep its community engaged? Contributors can leave at any moment.

- Confidentiality: Even with NDAs, it’s much harder to maintain confidentiality with non-employees. Given that there is a direct competitor out there (Hyperloop One), HTT may be concerned about its IP.

Meanwhile, Hyperloop One is taking a much more traditional approach to building the Hyperloop. It has 225 employees and has raised $140mm in VC money. But it has hit its own stumbling blocks, embroiled in internal turmoil which has resulted in the CTO leaving the company and suing the CEO for nepotism and gross mismanagement. Despite some early success (it has done a demo test in the Las Vegas desert – albeit, the test only lasted for a few seconds), it remains to be seen how well-positioned Hyperloop One is in comparison to HTT.

Meanwhile, Hyperloop One is taking a much more traditional approach to building the Hyperloop. It has 225 employees and has raised $140mm in VC money. But it has hit its own stumbling blocks, embroiled in internal turmoil which has resulted in the CTO leaving the company and suing the CEO for nepotism and gross mismanagement. Despite some early success (it has done a demo test in the Las Vegas desert – albeit, the test only lasted for a few seconds), it remains to be seen how well-positioned Hyperloop One is in comparison to HTT.

The value creation potential for Hyperloop is immense. Not only will a B2C model allow for dramatically increased geographic mobility for passengers (potentially transforming how we make our residential decisions – we will no longer be confined to live near our workplaces) and have important benefits for urban environments (e.g., reduced traffic), the potential B2B model could transform shipping traffic through ports and allow for substantially better and cheaper transportation of goods.

But is a crowdsourced approach the path forward? CEO Dirk Ahlborn certainly thinks so: “Hyperloop Transportation Technologies is more than a company, it is a movement. We have many people who followed their passion and joined the company at the beginning, working for equity making the company worth of millions.”

References:

Awesome post, Yezi. I completely agree with the challenges you outlined that Hyperloop faces. It’s definitely a one-of-a-kind sort of project where a figure like Elon Musk is able to rally such a talented group of individuals. To your point, unlike other crowdsourcing platforms, where individuals are able to contribute without necessarily impacting others involved, Hyperloop is a case where the end goal is one unified product. I struggle to see how Hyperloop will be able to successfully organize and make decisions on the overall vision given all of the people involved have different incentives in place and varied levels of engagement. Curious if you think Hyperloop will ultimately be successful and if this is a case for a new way of working and building product?

Building on Alice’s comment above – could cities and other governmental organizations play a role in the standards setting?

Great assessment. My immediate concern with the model is the question around execution – how do you deliver projects with this model? Innovation through collaboration has been proven to be successful, but with stock options belonging to the idea generators, how do you incentivize execution teams, if you have to bring them in? And who is the ultimate integrator?

Hi Yezi. Great post! I have question around the effectiveness of a crowdsourcing model for a Hyperloop concept. The design and development of Hyperloop is pretty much an engineering challenge. Hence, there is lesser amount of “creativity” involved and I wonder how much can a crowd contribute to it vs. an in-house engineering team. While I agree that the outward design and architecture of structures like Hyperloop can be crowdsourced…once this is fixed, I think the engineering solution to it is quite constrained and a crowdsourcing model might not be very beneficial. I am curious to hear your thoughts.

Think this is an interesting approach to the Hyperloop but ultimately for a project the requires a significant amount of R&D and real capital expenditure to get off the ground. I think you can crowd-source some of the initial design and simulation work as that can be all done digitally and at relatively low cost. But when you get the prototyping stage and more importantly the actual construction stage, who is going to be doing the work and managing the process. I don’t think you can part-time project manage a heavy CapEx project. I like the idea of utilizing a crowd to do the initial ideation, but at some point feels like a real company will have to get involved and take full ownership of the project.