Wounded Warrior Project: Not quite the hero we expect?

Wounded Warrior Project – charitable organization or successful marketing firm?

Wounded Warrior Project (WWP), a nonprofit that aims to “help injured servicemen and women aid and assist each other and provide unique, direct programs and services to meet their needs,”[1] is one of the most recognizable nonprofits in the post-9/11 era. One could arguably draw the conclusion based on the organization’s visibility, assets, and expenses that it is the leader of nonprofits that treat wounded warriors’ needs, but a closer examination indicates that it lags in its ability to blend its business and operating models and is in fact ineffective.

WWP explicitly states that its mission is to “honor and empower Wounded Warriors”: its business model is based on creating value for wounded warriors from post-9/11 conflicts who have returned and have unmet needs[2]. The organization boasts of 20 current assistance programs, and claims it will have supported 100,000 veterans and provided access to $96,000,000 in benefit entitlements (from the government, not WWP) by 2017, as seen in exhibit 1.

As the stewards of the contributions to WWP, the organization’s leaders and their operating model should allow for the allocation of a sizeable amount of the annual contributions to directly help wounded warriors. A closer examination, however, suggests that less than 50% of the yearly expenses, and less than 37% of the annual contributions are actually used to directly support warriors through interactive programs and support.

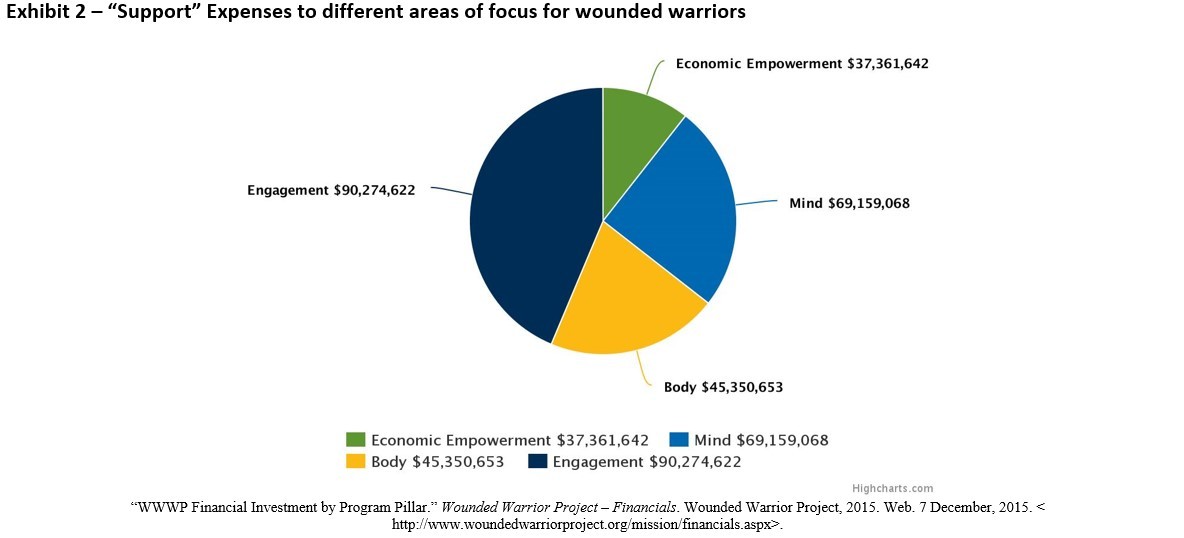

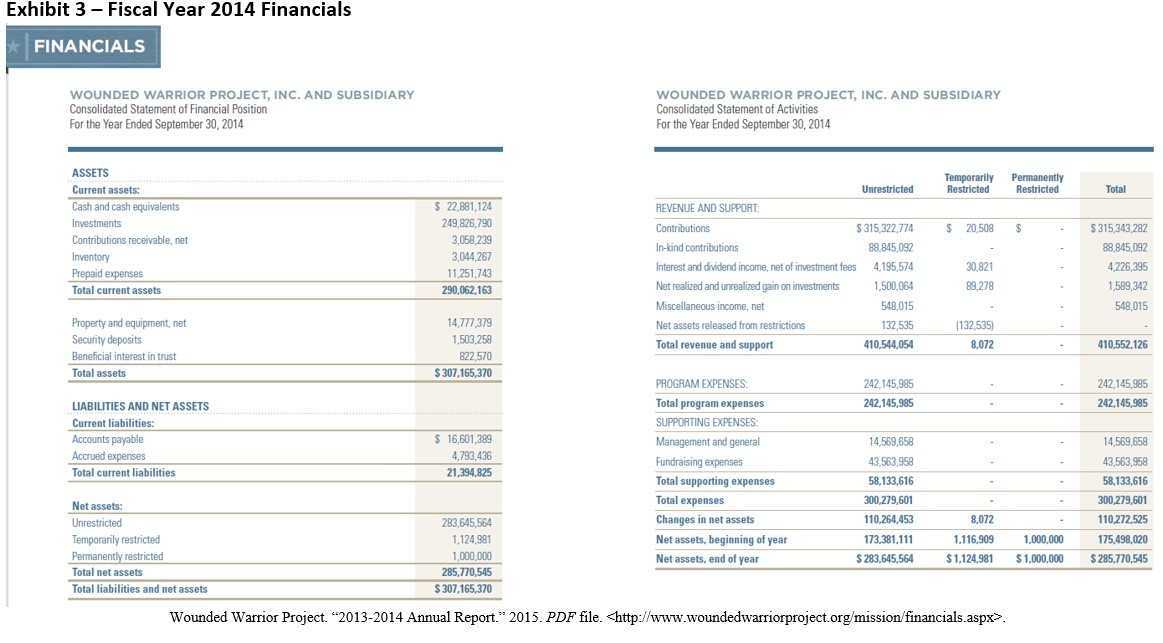

The operating model indicates a potential misallocation of funds to accomplish its mission and suggests the organization is in fact an extremely successful marketing firm that spends an exorbitant amount of money on marketing, consulting and other services, and salaries. This is contrary to the business model of the organization. As seen from the current financials (reported at the end of FY14), WWP received total revenue and support of $410,552,126 (exhibit 3). Its expenses for the period were $300,279,616, reinvesting $115,018,259 to build a treasure trove of assets to “hopefully” be used at a later date to support its charitable donors’ intended recipients. Exhibit 2 shows the claimed support given to each charitable program.

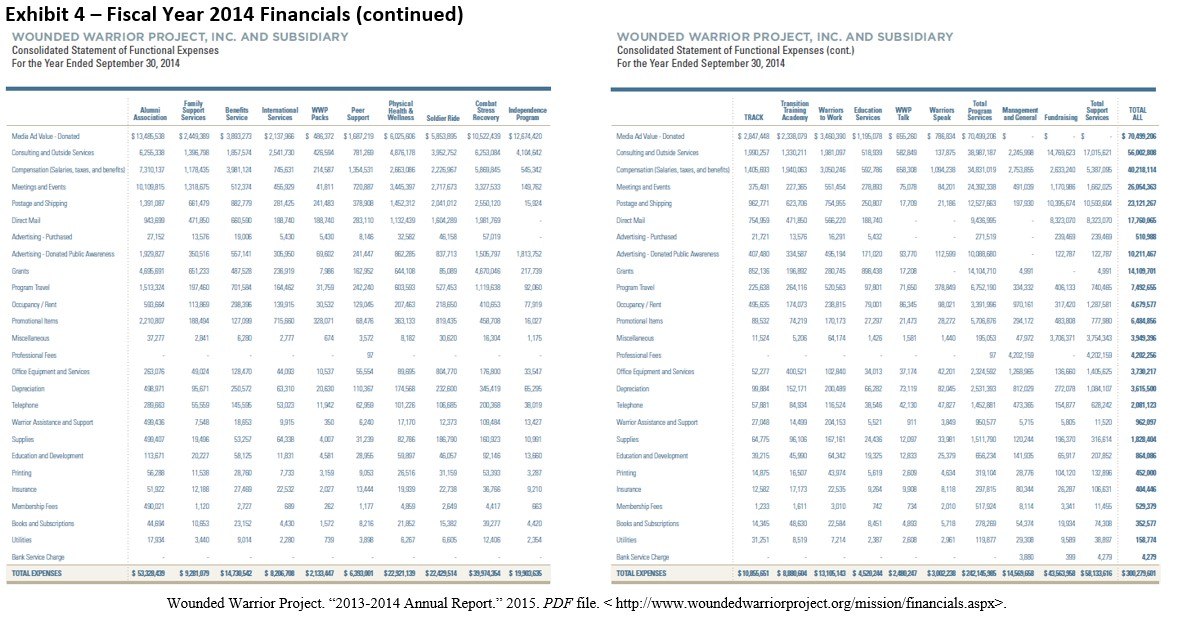

Of the $300,279,616 in expenses for the year, $70,449,206 was spent on media advertisements, $56,002,808 on “consulting and outside services,” and $40,218,114 on compensation (exhibit 4). Add $23,121,267 in postage and shipment, and $17,760,065 in direct mailings, and WWP has already spent $157,151,460 (more than 50% of total expenses attributed to non-material benefits for veterans). WWP also cites $43,563,958 in fundraising expenses, indicating that well less than half of the expenses are being spent to provide “direct” program support for wounded warriors. These numbers are staggering given the intention of the philanthropists who donate, hoping to support warriors in need of assistance.

If ones took a more optimistic approach to investigating the operating model of WWP, one could argue that its extensive marketing, mailings, and fundraising efforts have allowed WWP to sustain a competitive advantage by being one of the most prevalent nonprofits in the veteran space. One could also argue that the treasure trove that the firm has created could be used for future veterans and will grow in order to increase the number of programs in the future. Alas, with two conflicts having ended or having seen a significant reduction in troops, a more special operations/air support heavy campaign in the immediate future utilizing less troops, and casualty numbers significantly reduced over the past few years, chances are the number of wounded warriors will not skyrocket in the immediate future.

On a final note, the aim of the organization is inherently good, and its mission meets the criteria of what this nation’s wounded warriors need – support, assistance, and a chance for sustainability in the future – but its operating model does not match its mission. While Charity Watch (a website intended to educate philanthropists) rates WWP with three out of four stars, one must be diligent in understanding that while its transparency and governance receive four stars, its finances receive two[3]. A word to the wise: investigate the direct contributions of your charities to their intended recipients before donating.

[1] “To Honor and Empower Wounded Warriors.” Wounded Warrior Project – Mission. Wounded Warrior Project, 2015. Web. 7 December, 2015. <http://www.woundedwarriorproject.org/mission.aspx>.

[2] “To Honor and Empower Wounded Warriors.” Wounded Warrior Project – Mission. Wounded Warrior Project, 2015. Web. 7 December, 2015. <http://www.woundedwarriorproject.org/mission.aspx>.

[3] “Charity Navigator Rating – Wounded Warrior Project.” Charity Navigator. Charity Navigator, 2015. Web. 7 December, 2015. <http://www.charitynavigator.org/index.cfm?bay=search.summary&orgid=12842#.VmX-UIpdEog>.

Charities are tough: their operational model is part of the product and is open to a lot of scrutiny. This TED talk by Dan Pallotta (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfAzi6D5FpM) brings up the fact that people running massive charities (think the Red Cross) earn, relative to the heads of other large organizations, low compensation. This is largely because if they did get paid a lot of money, they would be criticized for it. The result is you end up with examples like the Wounded Warrior Project where the organization is inefficient because the human capital, while their hearts are in the right place, tends to be low relative to private sector organizations.

I found this article interesting because I have interacted and know many of the members of this organization who are working with wounded warriors. When I was at Brooke Army Medical Center they had representatives there and they did hand out free shirts and toiletry kits to soldiers, including me, when they were evacuated from theater. They also sponsored some rehab trips and movie outings, but it wasn’t until it was brought to my attention exactly how much they take it that I realized, as you point out, that not much goes back out. The really make no large contributions and have no major programs that justify the large exposure. I didn’t see you mention it, but part of there costs are attributed to suing other charities who used the name “wounded warrior” in their names or used any emblem that looks like black and white shadow of a soldier. This has caused a lot of people to also question their motives since they’re spending money to prevent other charities from receiving money that would go to veterans causes anyway.