Wasted Water: An Inside Look at AB InBev’s Water Risk Approach

Increased global water scarcity due to climate change poses a real threat to beverage businesses like AB InBev, who are under increased pressure to anticipate and mitigate their water risk in internal operations and supply chain

Current Water Scarcity Crisis

As an environmental science and public policy major at Harvard College, I’ve studied the real and growing water scarcity threat. Globally, 1.2 billion people do not have access to clean, potable water and over 4,000 children die from water-borne diseases every day.[1] Looking ahead, the Water Resources Group predicts a 40 percent freshwater supply gap by 2030.[2] One of the greatest contributors to the growing water scarcity crisis is climate change.

Climate change is altering the water cycle, affecting where, when, and how water is available, which has led to endemic natural disasters (e.g. floods and droughts), regional and international debates of water usage and quality, and rising water costs. [3] With exponential population growth and more water-stressed regions globally (see map below) [4], water-based businesses like Anheuser-Busch InBev (AB InBev), are under increased pressure to anticipate and mitigate their internal and supply chain water risk. This research assesses AB InBev’s, albeit limited, water risk approach and proposes recommendations for the firm moving forward.

Why AB InBev?

“Beer is the world’s oldest and most widely consumed alcoholic beverage and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea.”[5] While the beer supply chain is a long, involved process, the greatest input is water.[6] The average beer contains approximately 90 percent water.[7] In other words, it takes roughly 20 gallons of water to make a pint of beer.”[8]

Given that beer is mostly composed of water and water scarcity is a looming issue due to climate change,[9] it is more important than ever for companies like AB InBev, the largest brewer in the world, to understand how a brewery can mitigate water risk. [10]

Assessing AB InBev’s Water Risk Approach

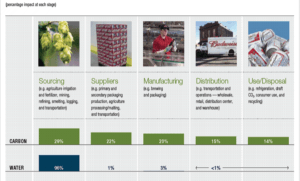

Water risks exist within a beverage company’s internal operations and supply chain. The figure below depicts AB InBev’s water and carbon footprint from upstream to downstream. As exhibited, over 90% of water use occurs outside of brewery walls through the sourcing process.

AB InBev closely monitors its manufacturing water use and has met progressive targets through an assortment of technological improvements, operational innovations, and awareness campaigns. For example, AB InBev’s system-wide approach to optimize efficiency is called Voyager Plant Optimization management system, standardizes processes and measurable standards for operations, quality, safe, and the environment in every AB InBev facility.

While most of AB InBev’s water use is upstream in the supply chain, the majority of the firm’s water risk mitigation efforts are focused on reducing their in-house manufacturing water use. [11] Looking outside the brewery’s walls, AB InBev is beginning to reduce its water footprint in supply chain operations by increasing communication and engagement with suppliers like barley farmers. Currently, AB InBev’s smallholder barley farmers in water-stressed regions like India and Mexico, operate in low infrastructure environments because they lack the economic incentive to invest in sustainable technologies. With a focus on the agro-business value chain, AB InBev management has started to measure the water footprint of farmers and malting plants to assess potential water conservation strategies. However, significant water stewardship efforts have not been implemented in upstream supply chain processes yet, which causes great risk to the company, especially in the light of climate change.

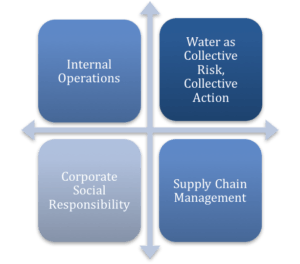

One reason why a market leader like AB InBev is not currently minimizing its total water risk across the supply chain, is potentially the tradeoff between the impact of the risk response and the control the company has over the response – see matrix below. Though breweries have full control over water use reductions in internal operations, these reductions have a low impact since only five percent of a brewery’s total water use occurs in-house.

Corporate social responsibility efforts, like awareness campaigns, have a fundamentally weak impact on the problem. Water stewardship in supply chains are high impact water risk responses, since 95 percent of a AB InBev’s water footprint is in the supply chain. However, AB InBev has less, direct control over the outcome of these responses. My recommendation is for AB InBev to pursue a high impact, high control water risk strategy which views its water input as a collective asset and risk across stakeholders.

Moving Forward

Breweries – like AB InBev – have an opportunity to lead the beverage industry in global water stewardship. In an era of increasing water stress and industry demands, breweries need to re-evaluate and distill their water practices internally and in supply chains.

Looking ahead, AB InBev should view water as a shared value and risk across the supply chain. While an individual actor, like AB InBev, might not see the ‘business case’ for addressing water risk in supply chains, that actor may have more leverage and impact if the risk of action is shared with other stakeholders in the supply chain.

(787 words)

[1] “Water for Life: Making It Happen.” World Health Organization. 2016. Web.

[2] Giulio Boccaletti, Sudeep Maitra, and Martin Stuchtey, “Transforming Water Economies,” McKinsey & Company, 2012, p. 1 https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/dotcom/client_service/Sustainability/PDFs/McK%20on%20SRP/SRP_09 _Water.ashx. 2016. Web.

[3] “Water Resources.” United States Global Change Research Program http://www.globalchange.gov/publications/reports/scientific-assessments/us-impacts/climate-change-impacts-by-sector/water-resources. 2016. Web.

[4] “Vital Graphics.” Global Water Stress and Scarcity. United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP). 2016. Web.

[5] Nelson, Max. The Barbarian’s Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. London: Routledge, 2005. 1-2.

[6] “Water Use: Thirsty Work.” The Economist. Web.

[7] “Beer Brewing; The Art and Science – Water.” Biochemical Engineering Department. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Web.

[8] Alter, Alexandra. “Yet Another ‘Footprint’ to Worry About: Water.” The Wall Street Journal. Web.

[9] “It’s in the Water.” Energy & Resources. Geotimes. Web.

[10] Anheuser-Busch InBev Annual Report. Rep. AB InBev. 2016. Web.

[11] Global Citizenship Report 2015. AB InBev. 2016. Web

This post was easy to follow and very enlightening when it comes to the process of beer production – I did not realize that “90% of water use occurs outside of brewery walls through the sourcing process”. Intuitively of course this makes when you think of the product, but the 90% figure really drove home the relevance of your post and why AB InBev should take the threat of water scarcity seriously. I would be curious to hear more about what a “high impact, high control water risk strategy” would imply. While this strategy sounds great in theory, your argument would have been more powerful if you had provided concrete actions and the the costs/benefits of adopting these. For example, does high control necessarily imply ownership of water production sources? Moreover, if you end up vertically integrating with regards to sourcing water how will you ensure against fluctuating water patterns – would you need to diversify your assets? You mention that “Globally, 1.2 billion people do not have access to clean, potable water and over 4,000 children die from water-borne diseases every day”. My concern is that this could potentially exacerbate country risk as governments prioritize access to water for their constituents over foreign corporations in extreme situations. In summary, there seems to be a large spectrum across levers like impact and control and it was not immediately clear to me what the implications of your recommendation might be.

Your idea is an intriguing one: by treating water as a shared asset and risk across its supply chain, AB InBev could increase its control over water sustainability efforts, and correspondingly increase its impact as well. I agree that AB InBev could have more credibility by putting its own skin in the game by sharing in the risk. Maria does make a good point as well however, essentially asking, how could this work in practice?

While it’s not immediately clear what the best way would be for AB InBev to approach its suppliers with what may be a difficult conversation, I would argue there is good reason to think this could work. AB InBev is a behemoth in the industry, and has substantial negotiating power over its suppliers. For an example of this, here is an excerpt from the book “Management” by Chuck Williams:

“One of the ways in which [AB InBev] leveraged [its] bargaining power was to tell its suppliers… that it would pay them for its product shipments 120 days after being invoiced. With existing contracts providing payment 30 days after being invoiced, that meant that AB InBev’s suppliers would have to wait an extra three months to be paid… [giving] AB InBev an additional $1.2 billion in cash flow per year, but… at the expense of its suppliers.”

In this working capital optimization conversation, AB InBev used its power to win at a zero-sum game: each extra day they took to pay their suppliers represented cash in their pocket that wasn’t in their suppliers’. If AB InBev can prevail in this kind of negotiation, it seems reasonable to expect they could also prevail in this water discussion. After all, all members of the supply chain can share in the reward of an industry-leading water sustainability effort, and the cost for this would be shared as well, making this more of a win-win.

Great piece, Smitha.

Perhaps I shouldn’t be, but I’m surprised that the economics of beer still support barley growth in water-stressed regions. I can’t help but wonder whether regions that have plentiful water supplies might be well-positioned to enter into the supply chain in the future. Anyone who’s ever toured a brewery has likely heard all about the source of water used directly for brewing. Brewers love to brag about the clean and local sources they use in their beer–but economics are absolutely a part of this story. Because brewers use a lot of water, they naturally gravitate to cheap water sources.

But even if the economics don’t support massive shifts in supply chain management for Big Beer, I wonder if craft breweries will take up the mantle. Microbreweries have already had a massive impact on beer sales, and consumer demand for organic/non-GMO foods has had a major impact on CPGs. Perhaps an enterprising microbrewery will shift to hydroponic barley production and make sustainable supply chain management is the next step in this consumer evolution.

Great article Smitha! I learned a lot, wouldn’t have suspected that 95% of the water consumption in beer is outside their direct control. I agree with the spirit of your recommendation – no point tackling the 5% and best to go after the 95%. I do foresee some significant execution risks though (which could be mitigated).

AB’s main lever to change water consumption across the value chain is its significant buyer power, as Dan pointed out. They can mandate standards which suppliers may be forced to adopt. However, while AB consumes a significant portion of the world’s water, they aren’t so big that they are the only game in town. I imagine MillerCoors, for example, is also a big water consumer.

In a supply-constrained environment, such as the world you imagine, supplier power increases, and with credible alternative customers such as MillerCoors, suppliers may simply allocate capacity away from AB in the long-run.

To mitigate this, AB could establish common standards with its largest competitors, “coopetition”, as standards would serve their common interest. In this way they can tackle the 95% of water use with a standards-based approach without jeopardizing their business.

This is so interesting, Smitha!

I would be interested in understanding whether more water is used in the farming input, or during the manufacturing process for the beer itself. As AB works to make it’s internal water use more effective, it would be interesting if they also explored changing beer preferences that use more water. As we look towards craft breweries, we find that they’re delivering a higher alcohol content in a smaller size. If AB could tap into this market, they could reduce their water consumption simply by changing their customers’ preferences given their size.

That being said, I think they will still have to follow your recommendations and explore decreased and more efficient water usage in their manufacuring change since it will be nearly impossible to change consumer behavior completely.

Smitha, great post and an interesting read! Definitely agree that the beer industry is one that faces considerable challenges due to its dependence on water as a natural resource. I was actually the campus rep for Anheuser-Busch for a couple years in college, and I was impressed by how focused they were as a company in ensuring sustainability, especially in regard to water usage.

I’m curious to see how Anheuser-Busch continues to innovate in sourcing its water, and I hope that it tests and explores more radical technology to drive sustainability long-term. I think sourcing is a key component of the water industry, as you’ve touched on in your post. For instance, they could explore water desalination to create a massive amount of potable water. If they invested in the technology, optimized overall operations, and achieved scale, there could be considerable savings in regard to the cost of water – savings which could be passed onto the consumer or the community.

They would also potentially save on shipping costs as a company, since they could source water regionally. If they created an adaptable technology that was easily transferable to new geographies, they could source from the closest ocean possible, unlocking savings in shipping and freight cost. This would be a bold step from where they are today, but it could be an interesting way to decrease their dependence on the current water supply and unlock potential savings for their business and customer base.