Redbox – “Disruptor” Finally Disrupted

Redbox pursed a high-fixed cost, capital-intensive model that – due to superior pricing and alignment with customer needs – allowed it to disrupt Blockbuster and other brick-and-mortar rental firms but crippled its ability to compete in an industry now dominated by streaming content.

On December 8, 2015 Outerwall (NASDAQ:OUTR), of which Redbox makes up >75% of revenue, plunged 23% on an aggressive earnings forecast slash and shake up of the Redbox management team[1]. This announcement likely signals the inevitable death knell for the “Blockbuster killer”, as its physical DVD distribution points struggle to stem the rising tide of streaming content.

Founded in 2002, Redbox pioneered the DVD-rental kiosk market. Prior, the brick-and-mortar rental model dominated, giving customers significant selection but charging high prices and late fees. As volume decreased, retailers increased prices to offset high fixed costs in a “death cycle” that opened up the market to disruption. Redbox entered with small-footprint kiosks located in high traffic areas (e.g., grocery stores) that limited selection to newer titles and only charged $1 per night for each DVD.

This innovative approach to fixed-point rentals, along with the rise of the Netflix subscription model, crushed brick-and-mortar providers, with Hollywood Video declaring bankruptcy in May 2010[2] and Blockbuster closing its remaining stores in November 2013[3]. At that point, Redbox owned ~50% of the physical DVD market[4] – we will see below why this Pyrrhic victory was short-lived as the operational decisions – juxtaposed with Netflix – made by Redbox set it up for failure:

Asset Utilization – To Centralize Inventory or Not to Centralize

Netflix took a centralized inventory approach – it spread a couple dozen distribution centers throughout the United States, so for a given N of a particular DVD the supply could service overall demand variations with less friction.

Redbox took the opposite approach – tens-of-thousands of individual distribution points each with a set supply of DVDs. For the same N of a particular DVD, the required precision to match supply and demand at an individual box to maintain high asset utilization was too title, demographic, geographic, etc.-specific. Therefore, in order to fulfill customer availability expectations, excess inventory – depreciating quickly after release – would have been required. Any inability to perfectly manage title permutations at a given location would exacerbate each other within the broader system, compared to the Netflix pooled approach. With limited ability to economically shift titles across kiosks, the utilization of an individual DVD would be “set” at the initial procurement and allocation decision; likely resulting in lower per-DVD utilization due to various levels of excess inventory. When inventory levels ran low, Redbox sent employees to purchase emergency DVDs at retail prices in Wal-Mart and Target. Up to 40% of overall purchases were done in this inefficient way.[5]

Fixed / Variable Costs – Costs to Scale

Due to its centralized inventory management, Netflix incurred very little cost beyond acquisition costs for an individual new subscriber. Instead, its model was burdened by high variable costs – namely postage costs for mailing DVDs. While this limited profitability in the short-term – the company expected to spend $600M on postage in 2010[6] – it created a flexible operating model, enabling growth.

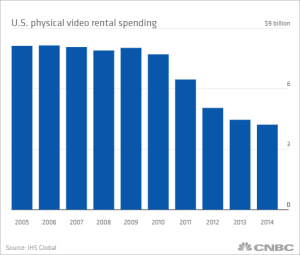

Redbox growth required expanding its kiosk distribution network. This approach created a two-fold fixed cost bind: first, it required significant capital to grow; second, each kiosk was burdened by both on-going servicing costs (e.g., locally optimizing inventory) and maintenance capex (e.g., replacing screens, upgrading interfaces). As Redbox kiosks proliferated, it is not a stretch to believe that the incremental kiosk was likely a.) less desirable and b.) cannibalized nearby kiosks. If you combine this with the shift away from physical rentals toward streaming (see graph), the volume decreases create a “death cycle” of fixed assets and lower per-asset profit that is no different than the pinch Redbox initially created for Blockbuster, et al.

Swimming Upstream on Streaming

With perfect hindsight, it’s not hard to imagine the industry shift toward streaming content. Additionally, when Netflix began streaming content in 2007, few appreciated the first-mover advantage and network effects associated with developing the dominant streaming content source.

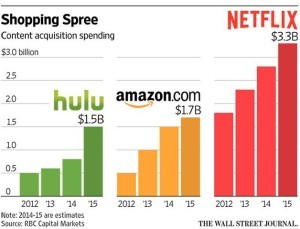

Redbox was disadvantaged from the start – it not only had to use its cash flow to service and invest in the physical infrastructure of its kiosks (discussed above) but also to support similarly capital-intensive coin-processing[7] and material-recycling[8] kiosk businesses. Furthermore, the company executed around $1B of stock buy-backs from 2010 – 2014 to appease investors.[9] Unable to make a “bet the company” plunge into streaming, Redbox finally got around to launching Redbox Instant in 2012[10]. At a similar price point to Netflix, with vastly inferior selection, Redbox hoped its partnership with Verizon would allow it to make up ground. However, it not only had to contend with Netflix but also Hulu, Amazon, et al. spending billions in aggregate on content (see graph below). At this point content acquisition costs were being bid up far above what Netflix had locked in as a first-mover. When combined with data infrastructure costs to support streaming, the new venture faced significant viability questions. Less than two years later, Redbox Instant was shut down in October 2014[11], leaving the company with only its legacy kiosk business and accompanying challenges described above.

Redbox attempted to provide cheap, convenient content to the masses. A shift toward streaming content should have been a “no-brainer” but its legacy operating model decisions and failure to move first doomed its ability to compete in an industry increasing turning away from physical content distribution.

Sources

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/09/business/daily-stock-market-activity.html?_r=0

[2] http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704608104575220370429528864

[3] http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2013/11/06/blockbuster-closing/3456271/

[4] http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/941604/000119312513173688/d524783dex992.htm

[5] https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20100204/1222178053.shtml

[6] http://techcrunch.com/2010/10/04/quora-netflix/

[7] http://www.outerwall.com/brands/coinstar

[8] http://www.outerwall.com/brands/ecoatm

[9] http://www.capitaliq.com

[10] http://money.cnn.com/2012/12/12/technology/redbox-instant-price/

[11] http://www.theverge.com/2014/10/4/6908181/redbox-instant-streaming-video-service-shutting-down-on-october-7th

Note: graph sources are cited within charts

Hi Will,

Thank you for the insightful post. In particular, I liked your description of how Redbox’s distribution method relative to Netflix made it much more difficult for them to manage inventory. I personally found that at the Redbox near my work, older titles no one had wanted in the first place were plentiful whereas hit titles that had just been released were always out of stock.

However, it seems to me that Redbox’s strategy still has some advantages over Netflix. One is the accumulation of recurring fees when customers don’t return their rental immediately. Another is the ability to rent console video games; game streaming services like OnLive have failed to stay in business, while Redbox’s game rentals should still be viable at least through the end of the current console cycle. Do either of these sources of revenue contribute significantly to Redbox’s top line?

In addition, I wonder if a move into streaming would have ever been possible for Redbox. Unlike Netflix, which shared revenue with content partners even in its early days, Redbox has always had an adversarial relationship with the film industry, which viewed Redbox as taking money away from DVD sales and contributing nothing in return. This tension may have made it difficult for Redbox Instant to source quality content. Do you think this could have been overcome even if Redbox had the capital to attempt a streaming platform earlier?

Adam

Thanks for the reply, Adam.

Revenue contribution for those two sources is not easily broken out but I would contend neither are “solutions” to the fundamental operating model issue.

Late fees are not a recurring source of revenue and may accelerate customer departure away from the physical DVD rental model – similar to what happened with Blockbuster, et al. I did not talk much about it in the post but the one advantage they had for awhile was renting new releases “on-demand” just down the street. However, given rise of true “on-demand” services (e.g., Comcast, Apple, Amazon) that rent new releases with greater convenience than before, I fear that Redbox will continue to shed volume until it gets down to its absolute core customer (i.e., the person that is actually only concerned with paying $1 versus $5 regardless of hassle, convenience).

Game rentals were a natural extension given the physical infrastructure was already in place. I can’t confess to knowing that much here but seems like services like GameFly are the natural Netflix in this industry. Additionally, given the higher price point per unit and likely more unpredictable rental period, I would think that all the issues I described regarding DVDs would just be exacerbated here. That being said, it does stave off the declining volumes if you can add new revenue to the same fixed asset base; so maybe I’m not giving them enough credit.

I think you are spot on regarding the relationship with the content owners and could have put an entire other paragraph in regarding the contrasting choices made toward channel partners that Redbox and Netflix made. I do still think they could have gotten there if they had made the move earlier, as content providers probably wanted to diversify away from a Netflix streaming monopoly even if it meant Redbox. However, after new entrants had already emerged, there was no reason in 2012 to give Redbox the light of day. Purely conjecture – they may have never been able to get there.

I enjoyed the very clear analysis on the centralized and capital efficient Amazon model vs the RedBox model. It seems that Redbox made a bet on low engagement consumers, and Netflix made a bet on high engagement consumers. I remember wondering this when the Netflix model was originally introduced: “Would people really bother to make this list of movies they wanted to see, wait for them in the mail, and then mail them back?” It seemed like a lot of hassle when you could just go down to Blockbuster. If I’m RedBox, it’s this mentality which drives me into a capital intensive kiosk model. Interestingly, my intuition probably would have been that RedBox made a good bet: generally speaking, I’d guess consumers are lazy, and prefer convenience above all else. I would have been wrong.

We are 100% in agreement – if we were writing this TOM Challenge in 2007, I could make a very compelling argument that Redbox was actually a fantastic success story. To me, the lack of foresight to attempt some transition toward online content and to repair damaged studio relationships (per Adam’s comment above) was the beginning of a slow erosion of the core business that has just recently started to come to a head. Also, I don’t totally blame them – if I’m looking at great kiosk return on investment and white space for miles, not sure I would have been able to shift either.

Will, really enjoyed the write up and analysis, thanks. I feel like I have personally made the shift from using Redbox more to using online streaming more. The main reason for me wasn’t purely convenience of streaming, but also earlier availability of movies. I’m not sure if this was a function of poor servicing by the local Redboxes near my home, or if there are different rules regarding the timing of releases for digital/hard copy, but there were a few occasions when I could rent something online that was not yet available at a Redbox near me. In either case, both would exacerbate the falling demand for physical DVD rentals that you highlighted. I also just checked out the stock and saw that it was at an all-time high in July 2015 before losing more than 50% of its value until now. Why do you think some investors missed this trend? Interested to see what strategy Redbox pursues now…

Thanks for the reply, Tyler.

I think the reason investors were able to look past the declining physical DVD rental space for so long is that the company still generates a significant amount of cash flow – even on a per kiosk basis – that makes the company an interesting opportunity to get good value if you believe that they will continue to buyback shares, accruing that cash flow to equity holders. If you think back to the Kerr-McGee case, there’s a lot of value to believing that the company will not use that cash to try to invest in other, riskier businesses (e.g., its ecoATM business described in the post) and/or will not try to plug the revenue gap by investing in additional kiosks. With a misaligned business / operating model, they would be “lighting money on fire” as I like to say – the recent revenue revisions probably made investors think twice about how sustainable that cash flow will be.