Open Innovation Startup Quirky Couldn’t Crowdsource Its Way to Success.

Quirky launched in 2009 to make the invention of consumer products more accessible. Open innovation helped usher in ideas from the masses and some would argue that crowdsourcing led to the company’s untimely demise.

The megatrend of open innovation has undergone many iterations since becoming more adopted in the early 2000s. The practice of organizations seeking contributions from an external community has spawned the acceleration of innovation among industry behemoths like Apple, General Electric and P&G. These market leaders endured significantly less risk with their crowdsourcing experiments than Quirky, a 2009 startup company founded by serial entrepreneur Ben Kaufman. Kaufman’s premise was to make innovation more accessible by creating a platform for users to submit product ideas in the home goods and electronic categories. The business model could be seen as a tech-enabled response to Joy’s Law, given the notion that most of the knowledge critical to innovation often resides past the boundaries of an organization, and the central challenge for those charged with the innovation mission is to find ways to access that knowledge.1

With a novel approach to open innovation, Quirky found early success and received subsequent capital investments totaling $150 million. The company was fraught with challenges as it scaled which resulted in a bankruptcy filing in 2015. The following year, the company had new financing and owners to embark on its second incarnation.

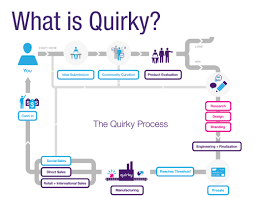

Since Quirky’s early days, open innovation was at the heart of the organization’s management of process improvement and product development. Quirky encouraged submissions from members as other members fervently shared their feedback. Quirky tapped into a concept Boudreau and Lakhani reviewed which stated that crowds are intrinsically motivated by the desire to learn as well as bolster their reputation with a given community.2 The company’s sophisticated online platform made it even simpler for members to feel a sense of gratification and achievement. By creating such robust software, the crowd had become a fixed institution available on demand to Quirky.2

The company implemented additional incentives for contributors to stave off criticism that crowdfunding resulted in many for-profit companies not appropriately compensating or acknowledging their contributors.3 Rather in Quirky’s case, users of the platform received “influence,” which denoted a user’s percentage-based contribution to an idea. Their level of influence was the equivalent to a percentage of royalties if the product went to market.

The original owners thought it would be best to have a vertically integrated company. Once an idea passed their initial criteria, Quirky funded the R&D, manufacturing, distribution and marketing. Each time, the company experienced a slew of problems in every phase of finding consumer adoption for products. Even more challenging, the cost of inventory when products didn’t sell at partner retailers like Target and Bed Bath & Beyond contributed to the company’s demise.

In the near term, the company’s new management has decided to continue leveraging ideas from the spectrum of crowdsourcing archetypes: The “professional,” who can contribute their academic/organizational knowledge, the “packager,” who draws inspiration from many places to create something unique of their own, and the “tinkerer,” who are just as capable as the professional, but would rather work on their interests on weekends from their proverbial garage.4 Looking further ahead, Quirky will no longer fund the tooling, manufacturing, distribution and marketing. Instead, it will license the products to companies like Shopify and HSN. 5

Based on Andrew King’s and Karim R. Lakhani’s findings, Quirky’s new management should consider internal crowdsourcing, which enlists ideas from employees.6 The past and existing model of external idea generation likely forces the company to have a surplus of employees simply to sift through the spectrum of ideas. With the sheer volume of ideas, a significant number of them would not pass Quirky’s criteria, thus the company could be more financially prudent by lowering its employee count. In their place, the company could hire fewer people who can ideate and execute a higher quality tranche of ideas.

Hiring employees with more expertise in innovation, product design/development could allow Quirky to position itself as a market leader in consumer goods innovation. With proper execution, the company could act as a consultant to larger companies needing innovation services, as well as implement its own version of Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT), which is Amazon’s online crowdsourcing system which distributes tasks to many anonymous workers.4

Questions

- Quirky’s rapid ascent and decline is another cautionary tale of heavily-funded startups that couldn’t create a profitable business off the heels of a megatrend such as open innovation. Given this outcome, its level of funding comes into question as a possible variable for its would-be success story: If they had raised less money, would the financial constraints have urged them to embark on a less scalable yet successful business model to avoid bankruptcy?

- When Quirky was founded in 2009, the economy was still reeling from the 2007 economic downturn. If the company had started in today, would the timing be enough of a variable for its first incarnation to have been successful?

(797 Words)

References

- Karim R. Lakhani and Jill A. Panetta, “The Principles of Distributed Innovation,” innovations / summer 2007.

- Kevin J. Boudreau and Karim R. Lakhani, “Using the Crowd as an Innovation Partner,” Harvard Business Review April 2013.

- Birgitta Bergvall-Kåreborn and Debra Howcroft, “Crowdsourcing and Open Innovation: A Study of Amazon Mechanical Turk and Apple iOS,” The 6th ISPIM Innovation Symposium – Innovation in the Asian Century, December 8-11, 2013.

- Jeff Howe, “The Rise of Crowdsourcing,” https://www.wired.com/2006/06/crowds/, June 1, 2006.

- Avery Hartmans, “Quirky, the invention startup that burned through $200 million and went bankrupt, is back from the dead with a new business model. ”, https://www.businessinsider.com/quirky-reborn-new-ownership-business-model-2017-9 , Sep 26, 2017.

- Andrew King and Karim R. Lakhani, “Using Open Innovation to Identify the Best Ideas,” MITSloan Management Review, Fall 2013 Vol. 55 No. 1.

Regarding your first question, I suspect a capital constrained Quirky would have pursued a much different strategy. The cost of vertically integrating and of taking on inventory risk would likely have been too daunting. To that point, the business might have landed on a model closer to the one they are pursuing now.

By getting out of the business of manufacturing, it seems to me that Quirky has essentially become a marketplace for consumer product innovation. I wonder if Quirky has spent enough time building demand from the manufacturer-side of the market. It seems that will be crucial if Quirky 2.0 is to succeed. Thanks for sharing!

Comparing the failure of Quirky to the success of Innocentive, a challenge-driven innovation platform, my opinion to your first question is that Quirky did not have a strong relationship with enterprises to monetise its innovative ideas. The funding pressures worsened the problem, but the business model itself may not be financially viable to begin with.

I definitely agree with the previous poster on the disposal of their manufacturing business. It is a detour that Quirky was ill-afforded to take since scale is a huge determining factor in manufacturing costs. I would love to see more on the economics of commercialising open innovation ideas, and if it will make sense for companies without the backing of traditional companies with deep pockets.

Like the previous poster, I question whether the Quirky business model makes sense to begin with. Do individuals submitting ideas have the same knowledge and capability to generate meaningful innovation as compared to industry experts. What if Quirky shifted from crowd sourcing ideas themselves to allowing large organizations to set up their own internal innovation efforts?

In 2012, the U.S. Navy stood up an organization known as the Chief of Naval Operations Rapid Innovation Cell. The “CRIC” allowed sailors to submit proposals and compete for funding for rapid prototypes of technology or processes that could improve maintenance, training, or operational effectiveness. The CRIC was eventually shut down due to bureaucratic competition, but not before it led to several advancements in cyber security, aviation, maintenance, and tactical systems. In the process, the CRIC leadership leaned heavily on innovation experts from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL).

Could Quirky pivot to help large corporations set up internal innovation cells to crowdsource ideas and monetize the expertise of the employees in a manner similar to how JHUAPL helped the Navy setup its innovation cell? Only time will tell. Until then, thanks for the great article!

For Quirky, crowdsourcing product ideas did in some instances result in a successful product in the market. For example Quirky’s “Pivot Power Outlet”(https://www.amazon.com/Quirky-Pivot-Outlet-Flexible-Protector/dp/B004ZP74UA) came out in 2010 (https://www.businessinsider.com/quirky-reborn-new-ownership-business-model-2017-9) and (at least this version) has in aggregate an almost perfect rating from over 950 customers as well as being named one of “Amazon’s choice” products. So while in this case the process of crowdsourcing to product launch was a successful one, it seems Quirky’s downfall was in missing the step of product-market fit or effectively assessing demand for that product before developing it further. Perhaps they did do research but it wasn’t rigorous enough, they used the wrong customer segment to test on, or they fell in to the trap of conformation bias. Either way, better demand-side research would likely have helped prevent the high inventory costs that were mentioned in this essay — costs that they incurred when products didn’t move at partner retailers like Target and Bed Bath & Beyond.

Very interesting article. With all the hype around some of these megatrends, it is eye-opening to see that they can also fail. IT is a learning opportunity that even with great potential, if it is not well executed it will not be successful.

I agree with the previous post that a likely reason for failure was insufficient market research. When crowdsourcing innovation, you gain access to a larger idea pool, but those ideas are still coming from a small sample of the population that may not be representative of the entire market.

The article, yet again highlights the fact that not every revolutionary idea makes it big. While many ideas may seem promising, what is crucial is a capability to even execute the idea on ground. In my opinion, Quirky did a great job interms of sourcing and evaluating great ideas in Phase-1, but overestimated its capability to launch the implementation that led to its demise.

Very interesting article ! Thank you for sharing.

Regarding your first question is too much funds the reason (or part of the reason) of their failure, I don’t believe so. My intuition regarding Quirky is that it was founded by a very charismatic leader that was able to sell a “dream”,surfing on this super trendy vague of open innovation. As inc.com puts it “Who wouldn’t love a scrappy New York City company that empowers a welder and grandfather from Larwill, Indiana, to dream up a step-on drinking fountain for dogs–and help him do the hard work of getting it designed, patented, and manufactured?”. (1)

However, I believe that the core mission of the start-up was flawed to begin with. I don’t think that the “crowd”, particularly the Quirky crowd, is a good decision maker when it comes to deciding which product to build, there are too much biases involved.

In addition, by nature their manufacturing was cheap, as such it made cheap products that were, I believe, hard to sell.

To conclude, I believe Quriky was a great example of VC biases when it comes to new innovation trends. When something becomes trendy, everyone wants to invest in it and people are biased in their analysis.

(1) What happened to Quirky, Inc.com, September 15 2015

Sounds like a very interesting business model! It’s interesting that crowdsourcing platforms like GoFundMe have produced so successful companies while this model, which relies on developing crowdsourced ideas internally, has faced so many challenges. I would suspect that part of the challenge is that no company, particularly a startup, can do everything well. It’s difficult to execute on a wide range of products bounded only by what users of a crowdsourcing platform deem desirable. There may also be a trade-off between relying exclusively on open innovation and learning. By using crowdsourced opinions as the ultimate barometer of consumer tastes, you are likely to miss important nuances that individuals with experience in product design and development for a particular product category may contribute.

I agree with much of what’s been said on the first question – that the surplus of funding they received probably pushed them to be very ambitious with growth. Had they not received that funding, that expansion strategy would not have been accessible to them.

I don’t believe shifting the timing of the their launch to a post recession period would have affected their success. My intuition tells me that launching close to a recession vs further out would impact the funding of business operations or the purchasing of their service because I would imagine during a recession there would be less money to go around. However, it sounded like they 1) received a lot of funding and 2) they were stocking the shelves of their customers (Target, etc). To me it sounded like their biggest problem was the product fit with the market. To me this raises broader questions around how can you harness the benefits of open innovation in a way that is profitable? The platform they built seems to have done a good job of elevating product ideas that may have been more novel and outside the box than something generated by individual companies with a more developed playbook. This probably happened much faster as well because of the crowdsourcing scale effects. A big learning from this company is that it may not be good enough to bubble up the innovative ideas, you will still need to filter and assess those ideas by economic viability and consumer demand.

I wonder if the idea of percentage “influence” could be applied to an academic or research setting? Open innovation for product development seems like a perfect fit for a university technology licensing office setting, where younger researchers could get their hands on a promising product and take some “influence” (read: financial stake) in the licensing process. Focusing on an academic setting could also help weed out unrealistic ideas, reducing overhead for Quirky.

The Quirky idea sounds quite intriguing, but to respond to our first question, yes, I think too much funding and ultra high expectations contributed to its bankruptcy. Rather than refining the business model to optimize the benefits of open innovation, Quirky tried to grow too quickly without a strong blueprint. Open innovation can bring significant benefits, but only if you set-up your business to take advantage of them.

I really like the idea of Quirky, especially the concept that the idea contributors receive royalties based on their idea. However, I agree with you that manufacturing the products and holding the inventory themselves was a bad move. Big manufacturing companies, like Johnson&Johnson should be able to post on the Quirky app (for a fee) and learn how to think like a consumer. Based on the influence point systems, Johnson&Johnson could even use this as a recruiting mechanism if a particular “professional” comes up with consecutively good ideas.

We see a similar point system on Quora – points based on the quality of responses. However, I struggle with the concept of allocating royalty based on idea “contribution.” I don’t think ideas are developed linearly. For instance, one person may have a great idea and then the next person may slightly build off that idea. How do you allocate points in that situation? 80/20? Seems like theres a lot of room for royalty debate, which could lead to litigation. Otherwise, I see potential with the Quirky product. Now, they just need to learn how to operate more efficiently.

This is a great example of a company that was not able to deploy open innovation entirely successfully. I think the democratization of ideas that comes with open innovation can lead to really interesting results, but should not be deployed without constraint. In this case, it was challenging for Quirky to deliver on both the ideation and the production/go-to-market of products. This seems too big a scope for even an established company to take on, much less a new startup. It will be interesting to see if they can grow profitably using a more limited model where their focus is on the first stages of product development.