“I wouldn’t trust them to build a canoe”: Building the Australian Navy

The rise of isolationism is putting pressure on the Australian Government to construct new Navy warships and submarines domestically. But can the Government really give a US$89B contract to an organization the Defence Minister has previously said he “wouldn’t trust to build a canoe”?

A $90B commitment and a choice between domestic or overseas production

The Australian Government plans to spend $US89B procuring nearly 40 new warships and submarines in the next 20 years, representing a doubling of the Government’s annual capital investment in the Australian Defence Force [1]. However, the Government faces a choice; should it commission the construction of these ships in Australian shipyards and support the local economy, or should it reduce the cost of the vessels by 40% by constructing them overseas or purchasing the them ‘off-the-shelf’ [2].

The economic implications of this choice are stark. Construction of the ships and submarines in Australia would support the beleaguered Australian shipbuilding industry, protecting 7,950 existing jobs and creating several thousand more over the next 20 years [2]. Alternatively, sourcing these vessels overseas could save up to US$30B [2], equivalent to US$3000 per Australian taxpayer, though this gain would be mitigated by the public costs associated with the likely collapse of the Australian shipbuilding industry.

Political considerations also loom over this decision. Historically, the current governing party has indicated it is open to overseas procurement of Navy vessels, while the primary opposition party has expressed “resolute opposition” to an overseas build [3]. The prior submarine program, the Collins Class, was constructed in Australia and was delivered late and over-budget, as well as being beset by technical issues that have at times resulted in the operational availability of the fleet being half that of comparable countries’ navies [4]. These issues have substantially dented the credibility of the Australian shipbuilding industry.

Committing long-term to a shipbuilding industry in Australia

The rise of isolationism as a political movement has put significant pressure on the Australian Government, resulting in a sharp shift in both policy and rhetoric. At the end of 2014, while arguing in support of procuring the submarines from overseas, the Australian Defence Minister stated that he “wouldn’t trust [government-owned shipbuilder] ASC to build a canoe” [5]. Yet, in 2016, the same Government announced it was launching a $US35B program to build the 12 submarines in Adelaide, Australia. The Australian Prime Minister announced that the submarines “will be built here in Australia … with Australian jobs, Australian steel, and Australian expertise”, and that the Government now held the view that “every dollar we spend on defence procurement as far as possible should be spent in Australia” [6].

The Government’s preference for domestic manufacture has continued for ongoing tenders. In March 2017, the Government announced the launch of a $US27B tender for the construction of the next generation “Future Frigate” that specified the location of the build as Adelaide, Australia [8].

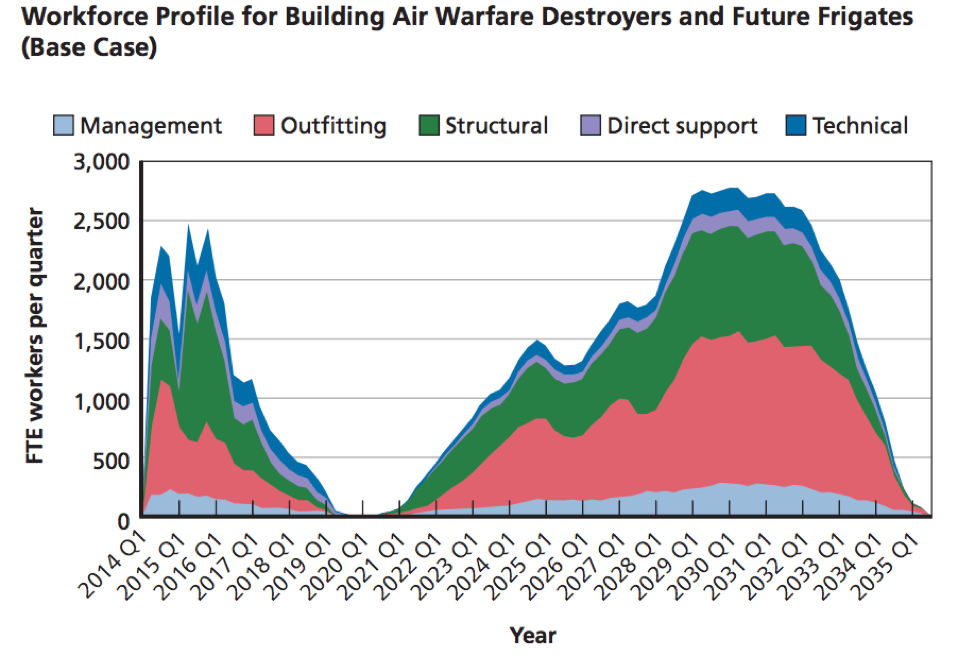

Further, in the absence of private sector demand, the Government has adjusted the planned construction timeline for the Navy warships over the next 10 years to eliminate a predicted demand gap or ‘valley of death’ in 2018-20. Smoothing the utilization of Australian shipyards avoids the loss of over 1,000 jobs in 2018-2020. [9].

Making the best of a domestic situation

The Australian Government has committed to supporting the domestic shipbuilding industry for at least the next 20 years. However, there are several steps it can take to minimize the overall cost to the taxpayer and preserve flexibility for sourcing vessels in the future.

- Leverage predictable demand to reduce Australian shipbuilding cost

The Australian Government should engage in a continuous-build strategy where predictable demand allows a “regular drumbeat” of the same type of ship to be produced in a facility. This will maximize the learnings gained from the first ships produced and increase efficiency over time.

- Avoid short-term over-expansion of the Australian shipbuilding industry

The cost-premium of domestic production is not equal across all ship types [2]. Accordingly, the Government should seek to utilize the existing domestic shipbuilding capacity to build ships where the cost premium is lowest (e.g., amphibious ships) and build other vessels overseas. This will avoid a short-term over-expansion of the domestic shipbuilding industry that would enhance the political imperative to protect it, and tie the hands of future governments.

- Explore labor reform in the Australian shipbuilding industry

The primary driver of the 40% cost premium of Australian shipbuilding is high labor costs compared to other developed countries [2]. Given the lack of competitiveness of the industry on a global stage, the Government should seek to reform the labor and union agreements in place at the Australian shipbuilders.

Questions for the class

- Is it acceptable for a government to spend taxpayer dollars on overseas goods when a domestic alternative is available?

- Should governments be held to different standards than private-sector organizations when considering overseas procurement?

(794 words)

References

- ‘2016 Defence White Paper’, Australian Government Department of Defence, http://www.defence.gov.au/WhitePaper/Docs/2016-Defence-White-Paper.pdf, accessed Nov 2017

- John Birkler et al, ‘Australia’s Naval Shipbuilding Enterprise: Preparing for the 21st Century’, Rand Corporation, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1000/RR1093/RAND_RR1093.pdf, accessed Nov 2017

- Daniel Hurst, ‘Tony Abbot pledges open tender for submarines to win over SA Liberals’, The Guardian, February 8, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/feb/08/tony-abbott-pledges-open-tender-for-submarines-to-win-over-sa-liberals, accessed Nov 2017

- David Wroe, ‘Our sub fleet world’s worst’, Sydney Morning Herald, December 12, 2012, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/our-sub-fleet-worlds-worst-report-20121212-2b97g.html, accessed Nov 2017

- David Wroe, ‘Defence Minister doesn’t trust Australian shipbuilder to make ‘a canoe’, Sydney Morning Herald, November 26, 2014, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/defence-minister-doesnt-trust-australian-shipbuilder-to-make-a-canoe-20141125-11tqv7.html, accessed Nov 2017

- Paul Karp, ‘France to build Australia’s new submarine fleet as $50bn contract awarded’, The Guardian, April 25, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/apr/26/france-to-build-australias-new-submarine-fleet-as-50bn-contract-awarded, accessed Nov 2017

- Brendan Nicholson et al, ‘Home-built submarines deemed too expensive, too risky, September 9, 2014, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/defence/homebuilt-submarines-deemed-too-expensive-too-risky/news-story/9c1915cf98b40dd1e7c44516cc2a1caf, accessed Nov 2017

- ‘$35 billion Future Frigate Tender’, Australian Government Department of Defence press release, March 31, 2017

- ‘The Government’s plan for a strong and sustainable naval shipbuilding industry’, Prime Minister and Minister for Defence joint press release, August 5, 2015

Paul — great post, on a topic that is close to “home” for you I am sure.

One topic that you mentioned briefly but allocated less airtime than I expected was the quality issue of domestic Australian production. Digging into one of your sources (4), I noticed that one potential “root cause” of the domestic production issues was “clear lack of a performance based culture”. In my mind, this incentive concept is exactly why the Australian government must entertain the thought of overseas production, or at least use it as a tool in negotiations. Government-owned entities with long-term contracts and little threat of competition often have less incentive to produce high quality outputs. At the very least, the Australian government should include performance incentives in their contract, even perhaps a clause that allows them to shift production overseas if quality issues persist. You asked whether it is acceptable for a government to spend taxpayer dollars on overseas goods, but one might also ask whether it is responsible to buy domestic if that means spending twice the amount of tax payer dollars on military products with quality concerns.

Thank you Paul. I enjoyed reading this post. I worked in the shipbuilding industry in my country during a consulting project and the nation was faced with a similar situation. Your question, “Is it acceptable for a government to spend taxpayer dollars on overseas goods when a domestic alternative is available?” really resonated with the project that I had worked on. My country was working on a project to build frigates (warships). The government was insistent that the ships should be built within the country indigenously. Yet there were quite some gaps when it came to technological infrastructure and know-how, which could significantly speed up construction. Producing domestically would mean increased delays and cost and less sophistication. At the same time, there was a strong requirement for indigenous manufacturing. Eventually, the country decided to work with an established international shipbuilder for transfer of know-how and technology alone but kept manufacturing restricted to domestic territories. To answer your question, in this case I just described there were several domestic alternatives. Were they the quickest? Not necessarily. The most sophisticated? Not really. In such circumstances, when you want to leverage the best practices that exist globally to optimize your own effort and investment, I think it makes sense to look at overseas options.

Paul, thanks for this. Really interesting dilemma faced by Australia. Am curious how much of the isolationism in this specific context is driven by the results of the UK Brexit vote and the 2016 US elections versus the increasing strength of Australia’s neighbors and the Obama administration’s “Asia Pivot”. I also wonder if this makes sense if the Australian government decides to build the capabilities internally for long-term independence versus a one-time project for potential political reasons.

Paul – very interesting and thanks for sharing! I had no idea about this problem facing the Australian Government, and I really appreciated your analysis. It is fascinating to hear that the Australian Government could realize 40% savings by outsourcing construction of their vessels. I think you did a great job too of presenting the tradeoffs for the Australian Government between producing this vessels at home versus outsourcing. The economy of Australia and local jobs would see a boon, but at a strong cost to the taxpayers.

I also think it was great that you refused to accept this false dichotomy – instead of accepting such expensive costs at home the Australian Government could reduce shipbuilding costs by: leveraging predictable demand, avoiding short-term over-expansion, and explore labor reform in the shipbuilding industry.

Putting my Kennedy School hat on, I wonder then if you think the isolationist movement in Australia might actually have beneficial results for the economy? It seems this political pressure is forcing the government to not only invest more in the local economy, but also look critically at their shipbuilding policies and how they can improve.

An interesting alternative is what India is doing with it’s current procurement of Dasssault Rafale’s from France. Dassault will be making 36 jets in Europe and then transferring technology to HAL (government manufacturer). It’s different in India because the labor costs are low and consequently there might even be benefits of local production, but it is a great way for the government to hedge it’s position.

To answer your question though – I do think the government has a responsibility to use procurement contracts to further social projects. However, it has to be worth the taxpayer’s money and set up the community for future success. It can be a powerful tool for affirmative action – for example, a lot of public bodies try to steer investment towards minority or women owned businesses.

There isn’t any inherent reason why Aus shoudn’t be a leading ship building and the government could structure this $90B investment as a way to stand up this capability.

Really well written piece, Paul!

I believe the decision on whether to invest locally comes down to how the Australian government views its priorities – either as stewards of Australian taxpayer dollars first, or as an agent for driving economic growth. In my view, the Australian government should invest domestically as a means of supporting the national economy. Particularly important in this instance is that the equipment is being used for military and security purposes. I had previously looked into technology companies supplying to the United States government, and there are often limitations to where the government can source tools from, given the sensitivity of the task. In my opinion, a similar approach should be used for shipbuilding.

You also laid out several thoughtful solutions for bringing down costs of production. In my opinion, your suggestion to explore labor reform is the most important one, as a first step in addressing the key issue – namely, that there is a lack of competition. While I am not familiar with the Australian shipbuilding industry, it appears that there is currently little incentive for builders to invest in more cost-effective methods or reduce the amount of labor content. To the extent that the government can reform its union agreements, it should then issue RFPs or contractors for its next generation of ships that prioritize contractors with greater automation, and higher productivity. While I believe there is a higher standard for governments to source products locally – particularly for a military purpose – it should not have to come at an inflated cost.

Paul, great article! It reminded me of day 1 of our finance class, when Prof. Cohen argued that the world as a whole is better off if markets are left to decide how labor should be spent in each country since that results in the biggest pie for everyone. Today it is the shipping industry that the Australian government is essentially subsidizing. What happens when other industries, such as automotive, ask for similar subsidies? If the goal is to save jobs, $30Bn for 7500 jobs seems to be quite a steep price to pay.

http://www.adelaidenow.com.au/rendezview/counting-the-cost-of-killing-australias-car-industry/news-story/cb10862b3405a9b26ce9f4541bbdbc08

Very interesting article, Paul. I’m particularly interested in your suggestion to “reform the labor and union agreements in place at the Australian shipbuilders” in order to reduce the labor costs to produce these ships in Australia versus overseas. I wonder if this would only serve to antagonize the shipbuilders, working directly against the goal of isolationism and maintaining shipbuilding in Australia. As to your question of whether it is acceptable for the Australian government to use taxpayer money for this project: I think it is acceptable to the extent they can show this is the best use of the $15 billion they’re losing due to manufacturing domestically. If this money could be spent on another initiative that employs an even greater number of Australians or gives a greater boost to the local economy, then this project becomes unacceptable.