Disrupting the education supply chain – can digitalization overhaul the K-12 factory?

Digitalization is flipping education on its head after more than 200 years.

A disastrous K-12 system

India’s National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) faces the un-enviable task of ensuring effective learning for 300 million K-12 students [1]. As the nodal body for school education reporting to the Ministry for Human Resource Development, NCERT is responsible for preparing textbooks and educational materials, organising training of teachers, developing innovative educational pedagogies [2], and supporting 1.5 million schools [1] to provide quality education. The situation today is dire – in 2016, only 48% of grade V students could read a grade II level text, and 50% of grade V students could perform subtraction functions [3]. However, digitization offers the opportunity to transform the traditional education supply chain.

Education has long followed the Industrial Revolution era model of linear assembly line teaching [5]. Inputs include students who receive a defined set of physical teaching materials through a prescribed and uniform pedagogy. The school is the factory and teachers are workers. The output is supposed to be student learning, measured at the end of the year through mass examinations and marked by credentials [6].

The flaws are glaring. Different students like to learn in different ways, using different materials and pedagogies, but are all taught in a standardized fashion [7]. Teaching materials are physical books, which are expensive and time consuming to print and transport, leading to multi-year cycles between updates. Teachers, faced with 40 students, have no choice but to follow a one-size-fits-all model. There is zero information flow and therefore no responsiveness – ‘customer’ feedback in terms of learning is only through the single assessment at the very end, and customer demand in terms of student engagement is never measured.

Digital disruption has started

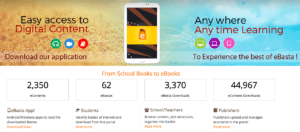

That digitalization of learning offers an unprecedented opportunity has been noticed. India’s New Education Policy draft, published in 2016, mentions the role of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in making knowledge easily available, aiding teachers and encouraging self-learning by students [8]. The NCERT has created digital books, an ‘e-Pathshala’ (online portal with digital content) and an online content repository ‘e-Basta’ which sources different types of content from different sources [9]. It is also using satellite technology for online lectures [10].

These innovations, provided teachers and students are trained to use them, can allow for quick cycles of content updates, lower cost of materials and more customization through provision of alternative content inputs for different types of learners. NCERT’s initiatives, once fully developed, will also allow diversification of content ‘suppliers’, allowing individual teachers, parents and organizations to make their own content accessible to many others.

The need for digital learning, not just digitization

However, these measures stop short of their goal, by focusing only on digitization of books, instead of true digital learning. I recommend the logical next step of replacing digitized books by interactive videos, which would allow users to engage with the content inputs. App-based tracking of viewership patterns would provide instant feedback on user demand, based on engagement with different pieces of content. Digital methods create the possibility of easily administrable and repeatable assessments, helping the software and teachers adapt themselves to customer feedback in terms of the level of the child. This form of personalized adaptive learning would give students control over their own education while allowing 10 million Indian teachers to become facilitators, rather than perpetually stretched between 40 students at different learning levels. Overall, education could be made non-linear – from a single product to allowing customers to order their own preferred products, in their own time.

These measures are easier said than done – we see very few successful examples even in the global North. To achieve success, NCERT will need to partner with private sector and civil society. Organizations such as Khan Academy and Ek Step are building out these advanced technologies and could work with NCERT to adapt them for the India government school context. Social enterprises such as Pratham and Mindspark are creating localized content and developing models to increase student engagement with technology. Only a collaborative effort can put the puzzle together.

Open questions

There are massive challenges even if the technology and content pieces are solved. Internet penetration in India is increasing but still limited, especially in the poorest regions; offline models can work but are restricted compared to their online counterparts. Digital literacy is low among students, but more problematically among teachers and parents – a lot of work will be required to develop the know-how and comfort to use digital models. Last but not least, how do you get first time, low-confidence learners, in unsupportive environments, to enjoy learning enough to engage with it consistently and under their own steam?

The road ahead is still difficult, but digital learning offers the opportunity to change the fundamental education model.

(787 words)

[1] Government of India’s Ministry for Human Resources Development Website, “Statistics Report” (2016)

http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/statistics/ESG2016_0.pdf

[2] National Council of Education Research and Training (NCERT) website (2017) http://www.ncert.nic.in/about_ncert.html

[3] ASER center, Annual Status of Education Report (2016)

http://img.asercentre.org/docs/Publications/ASER%20Reports/ASER%202016/aser_2016.pdf

[4] Davidson, Cathy, “Standardized tests for everyone? In the Internet age, that’s the wrong answer.” (Sep 23, 2011) https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/an-assembly-line-education/2011/09/26/gIQA8RJR5K_story.html?utm_term=.e9368e399107

[5] Chavan, Madhav, “Re-imagining India” book (2013)

[6] Christensen, Clayton, “Disrupting Class” book (May 14, 2008)

[7] National University of Educational Planning and Administration, “Draft Report on New Education Policy” (2016)

http://www.nuepa.org/new/download/NEP2016/ReportNEP.pdf

[8] NCERT e-basta website (2017) https://www.ebasta.in/content/about-ebasta

[9] Government of India’s Ministry for Human Resources Development Website, “ICT policy” http://mhrd.gov.in/ict_overview

Thanks for the thoughtful and well-researched piece, Azeez. I am a firm believer in leveraging technology to help k-12 students learn. I am concerned though about the growing inequality gap and how technology can contribute to this.

EdSurge wrote about this risk specifically warning institutions that teachers must be adequately trained to leverage technology appropriately in the classroom. [1] Moreover, most of a child’s education occurs at home. Even if students or classrooms have access to iPads or computers, it is unlikely that this technology will exist at home. This can impede a students’ ability to engage with the material.

Meanwhile, students in the right school with the right can excel. Therefore, one has to wonder if technology is really shrinking or widening the “opportunity gap.”

[1] Madda, Mary Jo. “Technology (and How It’s Used in Schools) Is Widening the Opportunity Gap.” Ed Surge, February 2016. Accessed November 2016. URL: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-02-10-technology-and-its-implementation-in-schools-is-widening-the-opportunity-gap

The debate around using technology in our school systems is certainly an interesting one – especially in places where we’re trying to achieve such massive scale and strong results. The key for me here is viewing technology as another tool, but not a silver bullet. An OECD study in 2015 showed that national school systems that invested heavily in technology haven’t done better than school systems that have been slower to adapt[1]. Technology definitely has a place in the classroom and we want students to be technologically literate to live in a modern world, but I worry that we view tech as a quick fix to education systems. Digital books is a great idea, but I worry about us thinking we can replace teacher interaction or student-student interaction with technology. These tools enable us to work better, but are they true replacements? There’s something to be said about the fact that even here at HBS, we’ve all opted in to a model that doesn’t allow for laptops or cell phones in the classroom. Granted, this is a unique experience, but there must still also be room for the traditional model?

[1] Coughlan, Sean. “Computers ‘do not improve’ pupil results, says OECD.” BBC News. September 15, 2015. Accessed November 25, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/news/business-34174796.

Excellent post, Azeez. While I agree that today’s education system should be reimagined in order to survive (and leverage) the relentless march of technology, we should be cautious in what we propose to fully replace. As more integral elements of elementary education are replaced with digitized technology, I am concerned about the social trade-offs we might make as a collective society. Literacy and the ability to continue one’s learning are the hallmarks of a sufficient education, but there are many other benefits that children redeem through a social, physical school environment. This is where children learn social norms, how to interact with others, how to deal with the adversity of the real social world, and how they fit into their own culture. Perhaps an integrated model that combines both digital learning with in-classroom social skills development is the answer. In any case, it’s about time we took another look at a centuries-old model of education, both in India and here in the United States.

India faces many of the same challenges that other countries have had to overcome when it comes to education, but two things that stand out as somewhat unique to the country are its sheer size, and the large variance of resources committed to education from region to region. India has 1.3 billion total people and a land mass only slightly more than a third of that of the U.S. Despite this, the population spends inconsistently on higher education, which is likely a result of variance in the access and quality of primary education. Across India, the average spend on higher education is “15.3% of the total household expenditure in rural and 18.4% in urban areas.” However, in the southern part of the country, the corresponding figures are 43% and 38% respectively. [1] This indicates that the southern part of the country islikely producing a vastly different number of students per capita that possess the skills necessary to attend a higher education institution. This is important to acknowledge and understand when considering how digitalization and education interact moving forward. Digitalizing an established education system is likely easier than digitalizing one that barely exists, but in terms of initial effort and resources, the part of the country with a weaker existing education system would likely benefit more per dollar spent on digitalization efforts, and therefore should potentially be the first to receive an allocation of what are very limited resources.

1. South india spends most on higher education education]. (2017, Jun 14). The Economic Times (Online) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/1908938808?accountid=11311

It’s exciting to hear that digitization is making an impact in Indian education; its ability to personalize learning seems well-suited to a country as large and diverse as India, and where class sizes frequently exceed 30 students. However, I’m worried that most of the innovation appears to be technical (i.e. better apps, more interactive videos) rather than organizational (such as changing the way teachers work, schools are structured, and so on).

Working as a consultant to US school districts, I saw two major challenges to the kind of personalization that digital tools promise in India. The first is principled: every student might be different, but they may be less different than is commonly assumed. For instance, there are likely only a few ways to effectively teach the Pythagorean Theorem, even though there are hundreds of different digital tools and approaches for doing so. The second challenge is practical: personalization is simply very difficult, in part because the existing tools are not very good and in part because using them effectively requires a very different style of teaching than most teachers are accustomed to. Just as we saw in Fabritech that the same employees who work well in a job shop may be a bad fit for an assembly line, so too may the same teachers who are great in a typical classroom struggle in transitioning to a digital one.

What both of these challenges have in common is an emphasis on the “people” problems, rather than just the “technical” challenges. I hope that as digitization progresses in India, these challenges will be given center billing, rather than simply focusing on the engineering problems.

Reviewing potential investments in traditional textbook publishers in North America, the effects of digitization on K-12 learning were evident. Digitization of textbooks, at least, appears to be the future, saving money and trees on printing and allowing students a more interactive learning experience. However, I still have several questions on the future of interactive digital education. First, the actual creation of the educational content remains a large portion of the cost of learning material. Will schools (or students) be able to cover the increased cost of materials when those development costs must be spread across a relatively smaller number of students in a more customized learning environment? Second, standardized tests are without doubt a measuring system with deep flaws, but they do offer the advantage of providing a basis on which to assess performance of one school or class versus another, providing a simple method for students, teachers, and schools to see how they are doing. In a more customized learning environment, how will any of these parties determine whether the methods that they use produce results? I agree that digitization is an exciting development in student learning with many benefits, but these issues will likely need to be solved before a more customized digital experience is adopted for students around the globe.

An interesting model for India might be Bridge International Academies, a social enterprise that has been rapidly opening schools in East and West Africa. Bridge equips teachers with electronic tablets and has its curriculum team constantly monitor teachers’ progress, send curricula updates wirelessly, and conduct A/B tests in the classroom to identify which pedagogies are most effective. It is doing this for very low fees, and it has partnered with the government of Liberia to provide these services at a large scale. While India is massively larger than any of the countries where Bridge operates, India could look for private schools that have effectively used digital technology for models to borrow from, or for partners in designing its own solutions. All the same, implementing these technologies effectively in public schools will be incredibly challenging due to the organizational weaknesses in India’s education sector.

It’s exciting to hear how much digitization has become a part of the thought process for improving education in many parts of the world. Thinking about my experience in a public school system abroad, however, I think that the biggest challenge is to get the hardware in place. As you noted, even though internet penetration may be low, this can be overcome with offline models. Without a hardware that will help access the content (whether online or offline), however, the struggle of educational coverage for such a large population still remains. In particular, as rural parts of India that need these resources most are also the ones that are most inaccessible (as we have learned through many cases covering rural India), hardware placement will be the key to this issue.

Completely agree with you that digitizing content of books is just a first step and the entire learning process has to be digitized for this to scale and achieve broad impact. To your question on adoption and digital literacy, I think offline and hardware will be essential to supplement digitized medium in the initial stage to boost adoption and educate all parties including schools, teachers, parents and students. NCERT should set up digital learning centers equipped with desktop computers and tablets in a convenient location in each town to provide access to the online content and generate awareness, familiarity and excitement around e-learning. Feedback should be collected to improve both the process and content. Also, training and engagement for teachers here is just as important as students – NCERT should introduce incentives for teachers to adopt technology in classroom teaching and establish public-private partnerships with organizations (both private education companies like Education First and non-profits like Khan Academy) to learn from their international experiences in rolling out digital education models.

Great read! I fully agree with your critiques of conventional teaching methods, which have largely remained unchanged for decades. The ability to instantly distribute, update and improve online education is a huge advantage and could significantly disrupt the conventional system. My main concern is about the inability for the digital platform to respond in a personalized way to the student’s particular needs. I believe that teachers will still have a role in the education system of the future. As you point out, they will become facilitators, but will still need to step in to understand and react to the physical, emotional and verbal cues from students who require support.

Really interesting! At my previous job, I did a consulting project for an NGO whose purpose was to improve the education of more than 10 million children in Africa. Exactly as you mentioned, since the NGO was funded by a telecommunications company, they were only focused on providing technology to the children rather than in the way how to teach them. The digitalisation of the economy is the future because it allows to customise the education for every children, even within the same classroom. The same way as in a game, the more intelligent students could advance to the more difficult lessons faster than the students who required more help. In this sense, teachers (a lack resource in Africa) could concrentate on the latter students.

Azeez, thank you for addressing the opportunities and challenges of digitization on the education supply chain. I wholeheartedly believe in the potential to leverage technology to personalize and enhance K-12 student learning. I agree that if India’s National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) can build the capacity to implement learning through interactive online videos, the data generated could significantly shorten the feedback loop between teachers and students.

The one-size-fits-all-model is outdated and ripe for disruption; however, I remain skeptical as to whether schools in India will be able to provide the hardware or basic connectivity to implement a new learning model for students. I believe NCERT’s effort to create digital books and an online content repository is an important first step in providing online learning options to the 300 million students it serves. NCERT must find ways to overcome India’s limited internet penetration and digital literacy across teachers and students. BYJU, an EdTech start-up based in Bangalore is also working on delivering personalized online learning experiences to children through a mobile app. With 8 million downloads, 400,000 paid subscribers and venture funding from Sequoia India, Chan Zuckerberg and others since its introduction in 2011, the business appears to be growing quickly. [1] I would like to understand how BYJU has been so successful given connectivity limitations in India and wonder if NCERT could gain any insights by studying BYJU’s effective digital content distribution model.

[1] https://www.vccircle.com/ed-tech-startup-byjus-story-now-a-harvard-business-school-case-study/

Azeez, thank you for the great article! I especially love seeing all of the past experiences and the knowledge that members of the section have and have shared here.

Initially reading your article made me excited about the possibilities of bringing education to more portions of a population where inequality is so stark. While it is extremely prevalent in India, I think that this is a problem affecting much of the world to include the United States. I focused more on the question of how to bring access and solid learning to underprivileged and underserved populations and thought that you raised many good points. While still a tremendous task, the infrastructure costs seem relatively easier to tackle. Providing internet access and the technological tools to classrooms, while prohibitively expensive, is still a capital issue. The real concern for me is how to foster adoption of this technology, and how to leverage its benefits without losing out on the social experiences of education that also make it so valuable. When we think especially of underserved populations, I worry that the adoption of technology, especially when that adoption is not reinforced in the home environment, may not be much better than what the current system provides.

Well done, Azeez. Extremely interesting application of a TOM framework.

Others have raised great points about the pedagogical strengths and limitations of personalized, digital curricula. If one agrees with the compelling educational argument that you laid out, then execution becomes the most important thing to consider. I think supporters of your viewpoint need to aggressively pilot their programs and test their hypotheses. In the United States, Rhode Island has been on the cutting edge of doing exactly that. As outlined in The Atlantic article linked below, the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act shifted significant power from the federal government to the states, specifically in the area of testing innovation. Rhode Island has used its increased autonomy to explore what possibilities digital, personalized learning might have for its 140,000 K-12 students [1].

While I cannot speak with any expertise as to the Indian political and social context, I imagine it is similar to that in the United States insomuch as an idea as radical as this will need robust evidence behind it. Adoption and promotion will need to be incremental and iterative. This is not a solution to rush to market. Fortunately for supporters of such innovation, that pace likely matches the pace of the underlying technological advancement.

On a separate note, I would not give short thrift to the power of shifting the paradigm on school textbooks. I am convinced that, but for twenty pound backpacks in elementary school, I would be two inches taller. More seriously, the shift to digital textbooks could well serve a dual purpose: long-term cost cutting and promoting technological literacy.

1. “Will Personalized Learning Become The New Normal?” The Atlantic, March 29, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/03/will-personalized-learning-become-the-new-normal/521061/, accessed December 2017