Closing Borders May Create a Wall That Boeing Can’t Fly Over

Can Boeing’s global supply chain survive a period characterized by isolationism?

In a time characterized by increasing isolationism, Boeing is at risk of enduring significant supply chain volatility and loss of international sales. As the number one exporter in the U.S.,[i] Boeing is heavily reliant on working relationships with foreign governments, the Export-Import bank, trade rules and tariff agreements (including NAFTA), and suppliers around the globe.[1] Boeing must persuade the administration to support global trade, work towards vertical integration, and bring engineering control back to the company to derisk future supply chain disruption.

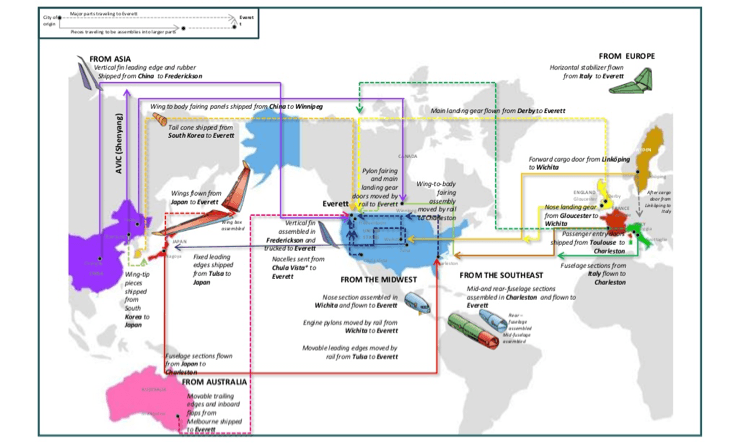

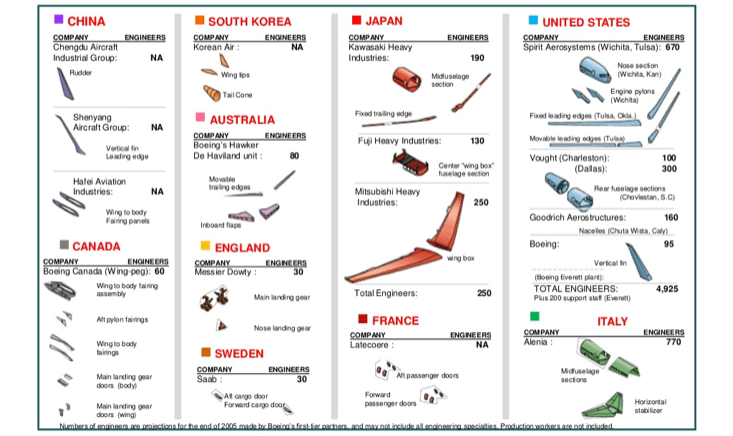

Boeing competes with French rival Airbus for the majority of the airplane market. Over time, Airbus has closed the quality gap relative to Boeing, which has led to airlines becoming increasingly price sensitive. The price sensitivity has led to a concern over supply chain disruption and cost. This is exacerbated on the 787 program, where Boeing developed a global partner strategy and outsourced more than 70% of the manufacture compared to the average 35-50%.[2] Boeing’s core competencies have traditionally been engineering and subsystem integration, but the strategy implemented on the 787 program entailed outsourcing the majority of integration and some engineering to the Tier-1 suppliers.[3] These changes make Boeing significantly more vulnerable to supply chain disruption, as Boeing no longer owns the engineering and integration needed to transfer work to a different supplier or bring the work back in house. The current administration’s threat to impose 45% tariffs on goods from China would likely lead to Boeing not being able to compete effectively with Airbus due to enormous supply chain costs.[4]

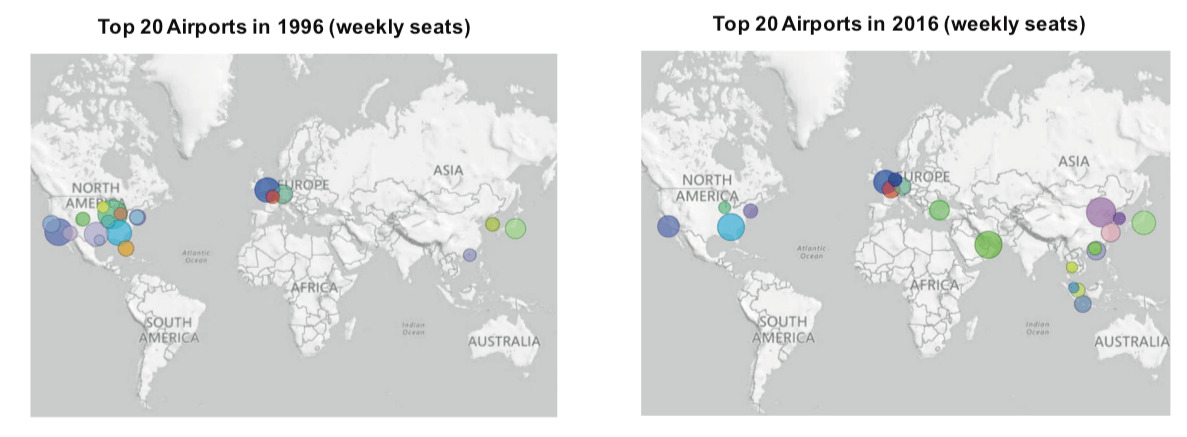

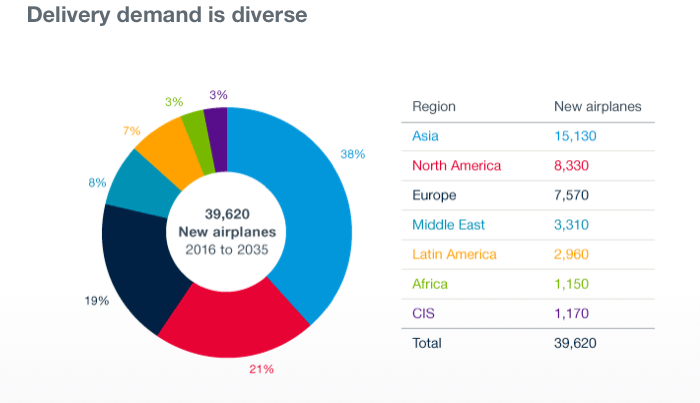

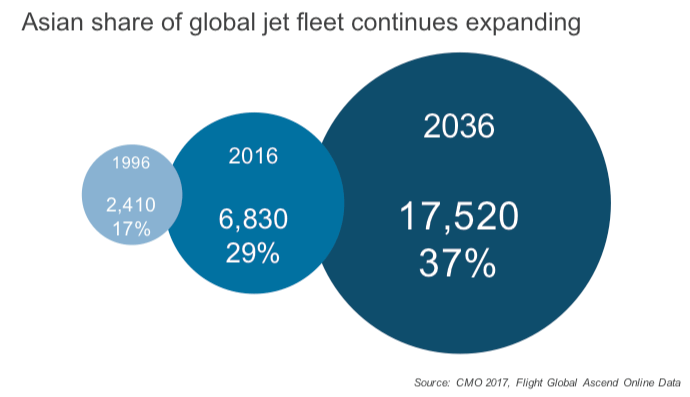

These proposed tariffs are equally concerning for sales. The Asian share of the global jet fleet was 17% in 1996, but is forecasted to be 37% in 2036.[7] These trade tariffs threatened against China could cause retaliatory action. Any change to the tariff structure or NAFTA could have a ripple effect throughout this complex global system. Finally, the administration’s reluctance to support the Export-Import bank would damage Boeing’s ability to sell planes worldwide.[ii] In its absence many airlines may turn to Airbus.[8]

In the short term, Boeing has focused on their bottom line in an effort to offset some of the volatility associated with the supply chain and international market. Boeing cut 8% of the workforce in 2016 to reduce cost.[12] Boeing lobbied heavily for the support of the Export-Import bank, and was ultimately successful.[13] This is a major win as it enables the Chinese market, which is expected to require 7240 new planes through 2036, valued at approximately $1.1 trillion.[14]

Boeing has also used the isolationist policy to its advantage. Boeing worked together with the administration to impose tariffs on the heavily government-subsidized Bombardier[iii] Cseries planes sold to Delta below cost. The International Trade Administration[iv] imposed an 80% tariff and a 220% penalty for improper subsidies.[15] This quickly resulted in Airbus purchasing 50.01% of the Cseries program, with an intention to locate final assembly of the Cseries in the U.S. to circumvent the tariffs.

In order to derisk the global supply chain in the current isolationist environment, Boeing must continue to work with the administration to emphasize the importance of global trade to the U.S. economy, calm supplier concerns, vertically integrate where possible, and bring engineering expertise back in house. In the development of the next airplane program, Boeing should adopt a strategy of removing any single critical point of failure within their supply chain. This does not mean that all suppliers should be redundant, or that there would not be costs associated with the loss of any given supplier. The single largest risk on the 787 program in the current political climate is the loss of a Tier-1 supplier, who owns engineering and integration of sub-tier supplier parts. If all engineering work at the plane level and subsystem level is brought back in house, and Boeing vertically integrates to the point of developing the subassemblies in house, they will be substantially less exposed to any volatility in their global supply chain. If the entire global supply chain consists of sub-tier suppliers creating parts to a Boeing-developed specification, Boeing can relatively easily switch suppliers if a problem arises. As an added benefit, final assembly has not been the most profitable segment for Boeing, so Boeing should become more profitable with a well-managed, vertically integrated approach.

All of Boeing’s options related to vertical integration involve expansion of the company. Should Boeing reverse the recent layoff trend and expand its engineering force? Should Boeing acquire tier-1 partners to support vertical integration, or build up the capability from within?

(755)

[i] By dollar amount.

[ii] The government-run Export-Import bank provides financing to foreign companies to support purchasing U.S. product when private institutions won’t provide financing.

[iii] Canadian airplane manufacturer.

[iv] A branch of the U.S. Commerce department.

[1] Johnson, Kirk. 2017. “Trump Talk Rattles Aerospace Industry, Up And Down Supply Chain”. Nytimes.Com. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/23/us/trump-talk-rattles-aerospace-industry-up-and-down-supply-chain.html.

[2] Steve, Denning. 2017. “What Went Wrong At Boeing”. Forbes.Com. https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2013/01/21/what-went-wrong-at-boeing/#571f9b0d7b1b.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Johnson, Kirk. 2017. “Trump Talk Rattles Aerospace Industry, Up And Down Supply Chain”. Nytimes.Com. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/23/us/trump-talk-rattles-aerospace-industry-up-and-down-supply-chain.html.

[5] “BOEING 787 US’s Dreamliner Or Nightmare-Liner? Who Will Ultimately Wi…”. 2017. Slideshare.Net. https://www.slideshare.net/Exolus/boeing-787-uss-dreamliner-or-nightmareliner.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Boeing: Traffic And Market Outlook”. 2017. Boeing.Com. http://www.boeing.com/commercial/market/long-term-market/traffic-and-market-outlook/.

[8] Carney, Timothy. 2017. “Boeing *Loves* The Export-Import Bank, But Boeing Doesn’t *Need* The Export-Import Bank”. Washington Examiner. http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/boeing-loves-the-Export-Import-bank-but-boeing-doesnt-need-the-Export-Import-bank/article/2615166.

[9] “Boeing: Traffic And Market Outlook”. 2017. Boeing.Com. http://www.boeing.com/commercial/market/long-term-market/traffic-and-market-outlook/.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Johnson, Kirk. 2017. “Trump Talk Rattles Aerospace Industry, Up And Down Supply Chain”. Nytimes.Com. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/23/us/trump-talk-rattles-aerospace-industry-up-and-down-supply-chain.html.

[13] “Trump Pick For Bank Of Boeing Faces Showdown On Capitol Hill”. 2017. Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-31/trump-pick-for-bank-of-boeing-faces-showdown-on-capitol-hill.

[14] “Boeing China Order Hawked By Trump Is Said To Be Mostly Old News”. 2017. Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-09/boeing-wins-china-orders-for-300-planes-worth-over-37-billion.

[15] Ostrower, Jon. 2017. “Boeing V. Bombardier: Tariff Is Now 300%”. Cnnmoney. http://money.cnn.com/2017/10/06/news/companies/boeing-bombardier-trade-ruling-tariff/index.html?iid=EL.

Thank you for this very interesting article! I definitely agree that Boeing should focus on bringing back in house its core competencies such as Systems Integration and Engineering not only due to looming trade restrictions but also because those are strategic skills that ensure Boeing a competitive advantage! By relying on Tier-1 suppliers to perform those actions, Boeing may be 1) giving away too much information and 2) “training” suppliers that may tomorrow start working for the competition. As you mentioned, Boeing can either focus on (re)developing those skills in house or vertically integrate its suppliers. I would argue for the second option as, even though it may be more expensive, it allows Boeing to foster international relationships and to show a commitment to international open markets. I believe that building these long lasting relationships is the only argument that could ultimately prevent a decline in orders from China should a severe trade tariff be applied.

Thank you for not referencing the potentially questionable airworthiness of new planes in this piece! Eerik’s article brings up many interesting points pertaining to Boeing’s decisions to outsource an increasing amount of the components of production to suppliers. This rise to 70% of outsourced manufacturing for the 787 program from traditional levels in the 35-50% range is a dramatic swing and exposes Boeing greatly to negative events in globalization. As Eerik looked at this problem, his recommendation was to work to bring much of this work back in house and to vertically integrate as much as possible. My worry with this, however, pertains to the increased costs required to drastically swing back to this model of production. Though Boeing recently laid off 8% of its workforce, Boeing would not only need to invest in training new people to handle this increased level of production, but would also have to invest in facility capacity to handle this. Eerik mentioned that Airbus’s rise in quality has led to an increase in price sensitivity job customers and I am worried these potentially drastic cost increases to curb fears pertaining to isolationist policies might lead to Boeing losing market share to Airbus on new orders.

Thanks for the really intriguing article.

The thing that surprised me the most about Boeing’s decision to increase outsourcing was the question we often talk about – “What business is the company in?”. As I understand, Boeing’s business model historically thrived on their engineering and manufacturing competencies. If 70% of the manufacturing is outsourced along with engineering IP, Boeing seems to be moving away from its core expertise and skewing towards more of a sales oriented organization! In my opinion, that is a severely undesirable move that dilutes their competitive edge against Airbus. Additionally, as Bruce mentioned, it exposes them to variabilities in the supply chain and the risks of IP infringement.

As pointed out already, reversing this trend is challenging and expensive. The question I want to raise is:

Can Boeing use automation to bring the manufacturing of currently outsourced parts back in-house?

This strategy will:

1. Capitalize on the company’s engineering expertise and give it further competitive advantage

2. Reduce variabilities in the production process with the supply chain being much less fragmented and dependent on externalities

3. Require R&D investments upfront but could pay-off with significant cost savings in the long-run

4. Avoid a requirement of a significant scale-up in the workforce

5. Avoid the risks from political uncertainties on a global supply chain

The risks could be:

1. Another dramatic change in the company’s strategy – is the organization culturally designed to be nimble to such frequent changes?

2. Disruption to the timely manufacturing and delivery of aircraft orders and the launch of new carrier platforms

3. Cost effectiveness of the automated in-house manufacturing process in comparison to outsourcing

Thanks Eerik for a very interesting post!

GE provides an analog to further support strategic reasons to bring more of the supply chain in house. Over the last few decades, GE has outsourced an increasing percentage of their production across their business units (much of it to Asia, especially for their largest steel and special alloy forged components). As a result, they’ve seen their own suppliers leap-frog them in technological innovation on those parts, and margins contracted. For example, GE purchases highly specialized airplane engine blades made of titanium super alloys. As the super alloys became more complex, GE essentially trained a couple of their suppliers to create them (and GE had nowhere near the required capabilities themselves), and thus the suppliers charged higher and higher prices and GE’s margins felt the squeeze. They are now faced with a difficult task of vertically integrating, and deciding if they should build or acquire these skills.

A question I have is whether or not vertical integration in this case also means ‘on-shoring’ back to the U.S., or if it is enough for Boeing to own the manufacturing abroad? Whether or not goods created off-shore continue to be considered American-made (in certain instances) [1] or as imports will make all the difference here, and it will be an important question given the difference in manufacturing costs here vs. abroad. It is a complicated topic and will no doubt have even more complicated proposed legislation, so management will have to watch closely!

[1] http://www.epi.org/blog/statistics-spin-foreign-goods-considered/

Really interesting article Eerik. I think that Boeing needs to decide whether it wants to be a manufacturing company or a marketing company. In the old days of the 707 and 747, my understanding is that Boeing was effectively vertically integrated, with functions ranging from design to manufacturing to assembly all performed in house. As Eerik notes, this has evolved significantly over time, with the most recent 787 program representing the most egregious example of outsourcing a majority of design and production to Tier 1 OEMs. Not only does this supply chain strategy pose significant risks from geopolitical perspective but it has significant cost and commercial implications as well. The 787 program is also known for its many years of delays and its significant budget overruns – almost $27 billion over original forecasts by the time the first plane was delivered. [1] The results speak for themselves. Even if vertical integration drives higher operating expenses in the short run, it smooths out longer term commercial risks and massively reduces the tail risks of geopolitical upheaval. As it turns to the NMA, Boeing should consider moving back to the production model that made its early planes and even the 777 so successful by bringing more jobs back in house.

1. https://www.seattletimes.com/business/boeing-celebrates-787-delivery-as-programs-costs-top-32-billion/

From one Eric to another, congratulations on a fine post. I disagree that Boeing should return more of its manufacturing for the 787 and future planes back to the United States. The global cost dynamics that pushed Boeing to take more of its manufacturing overseas have fundamentally not changed in the past decade. If Boeing abandoned this initiative they would find themselves in the same place a decade from now that they were in a decade ago – desperate to cut costs with a domestic unionized workforce.

I worry that these value-destroying tariffs between the US and Europe over Boeing and Airbus are only going to create a window for China or another country to develop a competitor and eat their lunch. China launched its first passenger plan earlier this year. [1]

[1] https://www.cnbc.com/2017/02/07/chinese-passenger-plane-to-rival-boeing-and-airbus-by-july.html