Berry Risky Business, Driscoll’s…

In the face of isolationism, how will Driscoll's continue to supply berries to anti-oxidant hungry Americans?

If you’ve stepped into a U.S. grocery store to find strawberries for a smoothie or blackberries for a pie, you’ve noticed Driscoll’s bold branding on your produce. Driscoll’s is the world’s largest berry producer [1] and prides itself on its “producing only the finest berries” through a network of domestic and foreign farms. However, the company may have some turbulent times ahead if isolationism affects its supply chain in two ways.

Labor Pains: Because of a shortage of American labor willing to perform the physically-taxing and meticulous work of picking U.S-grown berries in time for the market [2], Driscoll’s and other farms have become dependent on foreign migrant labor to harvest ripe produce. For example, over 160,000 temporary workers were admitted to the U.S. to harvest berries and other crops under this fiscal year’s H-2A visa (for temporary agricultural workers), a 20% increase over the prior year [2].

As the Trump administration considers curbing immigration to protect American jobs, Driscoll’s stands to lose a sizable proportion of its labor force if the H-2A visa program is cut and could see lower berry output from its U.S. farms. Because of berries’ short picking window and the intensity of labor required for the harvest process, even a week or two of labor scarcity could cause large-scale waste and rot on Driscoll’s farms. Under such circumstances, Driscoll’s would be unable fulfill its obligations to its grocery store customers and consequently to anti-oxidant lovers like me.

Produce Woes: In addition to its dependence on foreign labor, Driscoll’s grows about half of its produce across the border in Mexico. Two decades ago, Driscoll’s decided to extend its planting season by moving south of the border, where berries could be grown countercyclically and then exported to the U.S. during winter months [1].

Figure 1: Sample Growing Regions and Timeline for Driscoll’s Strawberries [3]

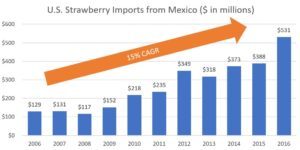

Because of similar actions by other U.S. farmers and the freedom provided by NAFTA, the U.S. fruit imports from Mexico have increased significantly, per the example of strawberries below:

Figure 2: U.S. Strawberry Imports from Mexico, 2006–2016 [4]

However, President Trump has hinted at tariffs of up to 20% to penalize Mexican goods imported into the U.S. to fund the proposed wall on the U.S.-Mexico border [5]. Under such a policy, Driscoll’s might reduce the load of Mexican berries it imports in the winter months, since its cash flows would be negatively impacted by the additional costs imposed by the tariff. In an alternate scenario, even if the company were able to pay the tariff to import the same quantity of berries as in the pre-tariff era and passed on the price increase to consumers, it could see decreased demand, and thus a negative impact on cash flow.

So, what are they doing…?

In the medium term, Driscoll’s is attempting to improve the harvest process by growing berries in substrates that can be raised to waist level [6]. This makes the berries quicker and less physically-taxing to pick, making the otherwise labor-intensive jobs more attractive to domestic workers and potentially increasing the company’s labor pool.

Figure 3: Waist-level substrate strawberries [6]

Figure 3: Waist-level substrate strawberries [6]

In the longer term, Driscoll’s is partnering with a company called AgroBot to build a robot to automate the berry-picking process, thus reducing the need for both foreign and domestic labor [6]. The future technology could be even more powerful if it can be combined with substrate-grown berries which are inherently easier to pick.

And what could they do…?

It’s unclear how the company is addressing the threat posed by proposed tariff; I believe Driscoll’s (and other U.S. farms with Mexican operations) could lobby to ensure that the tariff isn’t imposed by highlighting the higher prices that U.S. consumers would have to pay for produce. In addition, current headlines about immigration reform have mostly addressed illegal immigration, but it’s unclear what the path forward will be on visa programs that allow seasonal workers to work legally for Driscoll’s. As such, proposed lobbying could also ensure that temporary agricultural workers are included in protected visa categories under the reform, helping to prevent labor-led supply interruptions.

If the 20% tariff is imposed, Driscoll’s could export its Mexican-grown berries to alternate markets if evidence shows that demand is sufficient in such areas [7]. With China’s growing importance to global trade, for example, it’s not a stretch to imagine that it could absorb some of Driscoll’s otherwise U.S.-bound exports, assuming transportation costs aren’t prohibitive.

What else?

Can Agrobot’s robots truly replace or supplement human labor in a short while, given that they are currently “missing 1 in 3 berries” after years of development? [8]. In addition, has Driscoll’s considered adapting its berries species to improve their ability to grow in the winter, which could mitigate import-related risk during that season?

Word Count: 795

References

[1] Charles, Dan. 2017. February 16. Accessed November 11, 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/02/16/515380213/why-ditching-nafta-could-hurt-americas-farmers-more-than-mexicos.

[2] Driscoll’s, Inc. 2017. Where We Grow. Accessed November 11, 2017. https://www.driscolls.com/about/art-of-growing/where-we-grow.

[3] Whelan, Robbie. 2017. “U.S. Demand for Mexican Laborers Jumps — In the first nine months of fiscal 2017, number of mostly Mexican workers rose by 20%.” Wall Street Journal, August 9.

[4] Foreign Trade Division, U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. RELATED-PARTY TRADE DATABASE. Accessed November 13, 2017. https://relatedparty.ftd.census.gov/

[5] Gillespie, Patrick. 2017. “A 20% Mexico tariff would pay for the wall. But it would hurt Americans.” CNN, January 26. Accessed November 13, 2017. http://money.cnn.com/2017/01/26/news/economy/trump-mexico-tariff/index.html.

[6] Shanker, Deena. 2016. “The Berry of the Future Is Fed a Specialized Diet and Picked by a Robot.” Bloomberg, November 21. Accessed November 13, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-11-21/the-berry-of-the-future-is-fed-a-specialized-diet-and-picked-by-a-robot.

[7] Meyer, Gregory. 2017. “US farmers rattled by Trump’s Mexico plans.” Financial Times, February 7.

[8] Mohan, Goeffrey. 2017. “As California’s labor shortage grows, farmers race to replace workers with robots.” L.A. Times, http://www.latimes.com/projects/la-fi-farm-mechanization/

Berry interesting. It seems that the greatest vulnerability for Driscoll’s is the tariff risk. If this happens and Driscoll’s reduces imports during winter months, it is unlikely that U.S. winter harvests in Florida and Southern California could make up the difference. I like your idea of exporting the Mexican harvest to other countries – that had not occurred to me. However, U.S. consumers would feel such a winter supply decrease immediately and not be happy. Although a massive undertaking, Driscoll’s should explore the contingency of expanding operations in Florida and Southern California to become less reliant on imports from Mexico in order to meet winter berry demand.

This piece does a great job exploring the conflicting cost pressures the produce industry is facing as companies are often times tasked with choosing between the lesser of two bad outcomes. In the Salinas/Watsonville area over the past two years alone, the effective wage rates for harvesting crews have risen by over 30% due to factors mentioned by MJ including the back-breaking nature of berry-picking jobs and policies/ perceived immigration threats of the current administration. Though MJ details lobbying as a potential solution to the cost pressures of a tariff, my years in the produce industry have often shown its failure in this realm to make any tangible impact on policy makers. Unfortunately, the produce industry as a whole isn’t large enough or profitable enough to invest in lobbying activities like the corn industry. The solution, then, must come from company’s willingness to invest in innovation in both seed variety and harvesting methods. MJ mentions the potential for Driscoll’s to focus on seed variety, but luckily, this is something Driscoll’s currently invest HEAVILY in. A typical Driscoll’s seed variety takes up to seven years for development and is only sold in retail channels for roughly three years before it is replaced by a superior seed variety. If there are any possible advancements in seed technology, Driscoll’s most likely already has it under development. In addition to Driscoll’s work in improving seed variety and harvesting, location of its sourcing will be something to pay close attention to in the future. As costs continue to rise in California, will the current supply chain model be disrupted in efforts to find lower cost solutions internationally?

Ironically yesterday, I watched Boston Dynamic’s Atlas robot complete a backflip at the quality level of a human – so I definitely believe in the ability for robots to complete labor activities in the berry industry. Like Kevin, my biggest concern is Driscoll’s exposure to a potential tariff risk. Although, I believe the solution would be to just pass along the increased cost to consumers. In my opinion, consumers are already accustom to paying a higher price to obtain berries in winter months since they are aware that they are not grown in the US during those months.

I strongly believe that Driscoll can use robot to reduce some of the intensive labor aspects, but this isn’t the only solution that they can use to mitigate potential labor force reductions. Driscoll could launch job campaigns to attract new employees. I think there are still individuals in the US that would be willing to work in a labor heavy industry – it is just on Driscoll to find those individuals through marketing and WOM.

I find it really interesting that Driscoll’s is investing in automation. Essentially, they are shifting their business model from high operating costs (ongoing labor) to high capex costs (machinery). While automation seems like a potential solution to rising labor costs, I wonder how Driscoll’s will handle this shift. How will they finance the investment in capex and what do they expect the lifecycle of the machinery to be? How will they collaborate with machinery suppliers on the product development process?

Another main concern I have with automation is whether it will even be effective – the stat you mentioned (robots missing 1 in 3 berries) is shocking. It seems doubly expensive to invest in robots that cannot do the job and hire workers to pick the berries that the robots missed.

Finally, it will be curious to see how Driscoll’s handles the people element. They will need new skills in their workforce to coordinate robot usage across farms (to maximize utilization), drive innovation, and operate new machinery. Investing in automation is expensive (both from a capex and people perspective), and with the low quality of robots today, I’m not sure if the investment will generate positive ROI until years down the line.

A very well-written and concise article.

I’m a fan of using the Agrobot if we face a shock labor shortage. Even though it’s not 100% efficient (missing 1 in 3 berries), we might just need another worker or two to do a sweep of the remaining berries after. In the long run, I still see the Agrobot as a possible cost-saver by replacing a number of workers. This might even be cheaper than raising the berries to waist level (not sure how raising the berries might affect drainage, quality etc.)

On the other hand, I’m not so sure about re-engineering the berries to have them grow in winter. For sure, this will ease the pressure on supply especially during the holiday season, but will the re-engineered berries cause a consumer outcry? Consumers may not like the idea of a genetically modified berry especially when Driscoll’s prides itself on the finest quality berries. Furthermore, the engineering, testing and approval process might take years before they can reap the fruits of their labor.

Kevin’s “Berry interesting” nailed it! I really enjoyed this read. I understand that automation seems like an appropriate response for labor shortages, but I do wonder what impact this has on the individuals whose lives depend on working in agriculture. As you mention, many folks are tired of dealing with this “labor headache” (as one agriculture sales manager describes it in the article below). Automation can help make results more consistent and manual labor-independent, but as population increases, I think we need to remember that the agriculture industry could be an incredible opportunity to maintain and create jobs for people both at home and abroad. I also think customers appreciate the “hand picked” human element that is often associated with agriculture–and perhaps a large reason why lately, local farms and organic foods have become increasingly popular. Ultimately, even though it may help the business to rely on automation as a result of pending immigration issues, I would personally suggest more reliance on human labor, even if it comes at a higher cost. This could happen through lobbying with the government or turning to more local sources of labor in order to support people who do not have other opportunities to make a living. Thanks for sharing your article!

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trump-effect-agriculture-automation/as-trump-targets-immigrants-u-s-farm-sector-looks-to-automate-idUSKBN1DA0IQ