An Explosion Redefines a Worst-Case Scenario

Con Edison’s 13th Street Power Facility erupts in light as water floods the station. Half of Manhattan goes dark and Hurricane Sandy rages on.

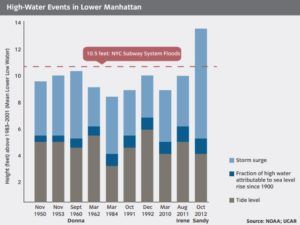

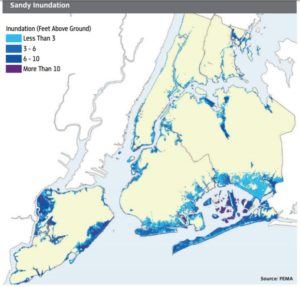

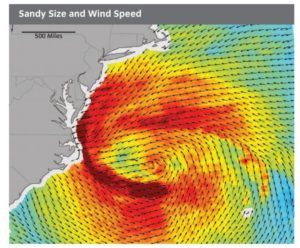

On Monday, October 29, 2012, an explosion rocked the 13th Street Power Facility near the East River, cutting off power to much of lower Manhattan. Water levels had risen fourteen feet as Hurricane Sandy (“Sandy”) battered the East Coast in what was to become one of the worst Atlantic hurricanes on record. The storm tide waters generated by Sandy had not been seen since at least 1700,[1] and the power station’s flood walls, which were built to withstand twelve feet of floodwater, were useless.[2] Power would not be restored for days, as people in Manhattan operated without access to elevators, heating and in many cases, water, during a particularly cold Autumn.[3][4]

Con Edison (“ConEd” or “the Company”), a subsidiary of Consolidated Edison, Inc. (NYSE:ED), is the utility company accountable for the 13th Street Power Facility and is also responsible for providing electricity, gas and steam to most of New York City and Westchester County, NY. It would take ConEd a week to restore power to 87% of their customers who lost it, and a total of two weeks to restore power to all of their customers.[5][6] The infrastructure weaknesses that led to the power outages were a consequence of poor weather forecasting and institutional shortcomings at ConEd. As climate change persists, weather events are expected to become increasingly extreme and unpredictable. In fact, the four largest storm-related power outages in ConEd’s history have all happened since March 2010.[7] Many of ConEd’s structures are built to withstand worst-case scenarios, but unfortunately, the bar for the worst case has moved quickly as climate change accelerates. ConEd’s lack of foresight led to the flooding of the power facility, as the flood walls had been built using projections from outdated storm models.[8]

Further investigation uncovered other institutional flaws that led to these failures. At the time, ConEd had a policy to “run it until it fails” which led to systems featuring old components and deteriorating physical infrastructure. Exacerbating issues further, ConEd failed to staff sufficient manpower to conduct needed preemptive maintenance work due to a lockout of certain staff in the summer of 2012. These problems were and still are emblematic of the issues faced by many utility companies throughout the United States. Unfortunately, poorly managed post-Sandy repair efforts will most likely lead to future problems for the ConEd. In the urgency of restoring service, ConEd resorted to temporary repair arrangements that were not properly documented and therefore will be near impossible to revisit. Also, the use of out of state aid workers accelerated repairs, but sacrificed quality. Many of the volunteers were improperly trained and not well versed in New York’s complex electrical systems.[9]

Although Sandy was an extreme weather event, it showcased how ConEd had failed to stay ahead of the possible consequences of climate change. If ConEd is to avoid catastrophic failures going forward, it must rectify the systematic internal failures that Sandy exposed. In February 2014, sixteen months after Sandy, ConEd committed to incorporate plans to protect its power system from the effects of climate change as part of a new multi-year $1 billion investment plan. These “storm hardening” funds were to be deployed to areas where ConEd was especially vulnerable. For example, Manhattan customers would receive investments in flood prevention, while mainland customers would receive protection from falling trees. The Company revised its flood protections standard by adopting the most current FEMA hundred-year flood level estimates plus a safety cushion of three feet. ConEd furthermore committed to undertake a study on how climate change would affect its electricity, natural gas and steam systems in the coming decades, and how to prepare for these changes going forward.[10]

ConEd financed these projects without concurrent price increases to its customers, and this drives to the heart of the challenge related to motivating preemptive catastrophe investment within infrastructure companies.[11] Customer pricing for infrastructure companies is often restricted by government policy, therefore managing costs becomes the main avenue through which these companies can increase profitability. Tightly managing costs most often leads to a reduction in quality. Moreover, any capital investments are hard to value since they do not explicitly increase cash flows after completion. By design then, it is the responsibility of the state and local governments to either mandate investments or provide incentives to invest through tax breaks or looser price ceilings. The steps ConEd is taking to better understand its risks in the current climate environment are adequate, but still reactionary rather than proactive. Loosening the Company’s margin constraints should hopefully push ConEd to plan not just for its immediate future, but to look forward to the next hundred or two hundred years as it anticipates the arrival of Sandy v2.0. (779 words)

[1] P.M. Orton, T.M. Hall, S.A. Talke, A.F. Blumberg, N. Georgas, & S. Vinogradov, January 25, 2016, “A Validated Tropical-Extratropical Flood Hazard Assessment for New York Harbor,” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2016JC011679/epdf, p. 1-4, accessed November 2016.

[2] Stephen Gandel, November 12, 2012, “How Con Ed turned New York City’s lights back on” Fortune, http://fortune.com/2012/11/12/how-con-ed-turned-new-york-citys-lights-back-on/, accessed November 2016.

[3] Con Edison Newsroom, October 30, 2012, http://www.coned.com/newsroom/news/pr20121030_2.asp, accessed November 2016.

[4] City of New York, “Sandy and Its Impacts,” http://www.nyc.gov/html/sirr/downloads/pdf/final_report/Ch_1_SandyImpacts_FINAL_singles.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[5] Con Edison Newsroom, November 5, 2012, http://www.coned.com/newsroom/news/pr20121105_4.asp, accessed November 2016.

[6] Con Edison Newsroom, November 12, 2012, http://www.coned.com/newsroom/news/pr20121112.asp, accessed November 2016.

[7] Bobby Magill, “New York – Con Ed Settlement Sets Stage for Climate Change Reform by Power Utilities,” Pace Academy, March 1, 2014, https://earthdesk.blogs.pace.edu/2014/03/01/new-york-con-ed-settlement-sets-stage-for-climate-change-reform-by-power-utilities/, accessed November 2016.

[8] Con Edison Newsroom, 2014, http://www.conedison.com/ehs/2014-sustainability-report/, accessed November 2016.

[9] Utility Workers Union of America & UWUA Local 1-2, February 2013, “The Impact of Hurricane Sandy on Consolidated Edison of New York: Assessment of Restoration Efforts and Recommendations for the Future,” http://uwua1-2.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/CLICK-HERE-to-read-the-Position-Paper-of-the-Local-1-2-on-Hurricane-Sandy.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[10] Ethan I Strell, “Public Service Commission Approves Con Ed Rate Case and Climate Change Adaption Settlement,” Columbia University, February 21, 2014, http://blogs.law.columbia.edu/climatechange/2014/02/21/public-service-commission-approves-con-ed-rate-case-and-climate-change-adaptation-settlement/, accessed November 2016.

[11] David Funkhouser, “Con Ed Agrees to Climate Change Plan,” Columbia University, February 24, 2014, http://blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2014/02/24/con-ed-agrees-to-climate-change-plan/, accessed November 2016.

[Images] City of New York, “Sandy and Its Impacts,” http://www.nyc.gov/html/sirr/downloads/pdf/final_report/Ch_1_SandyImpacts_FINAL_singles.pdf, accessed November 2016.

Great post Hugo. My main concern with any regulated infrastructure asset is how the owner can articulate a case for upfront investment in a political/shareholder environment that is often quite reactive vs proactive. I think there could be a way to align the financial reality of needing to invest on a consistent basis with the randomness with climate events, perhaps by investing in catastrophe bonds or catastrophe reinsurance to provide sharp cash inflows during times of crisis to offset steady investment outflows. This could help make a utility’s cash balance more “climate neutral” and make the case for investment easier for both shareholders and regulators

Interesting read, Hugo. This reminds me of what I often had to deal with in Florida where, despite adequate hurricane preparation, power outages were always expected. Florida Power & Light (equivalent to NY’s Con Edison) has invested significant capital (over $2B) in developing new technologies to better respond to storm damages and prevent widespread power outages [1]. Specifically, they have invested in amphibious robots, drones, and mobile technologies to allow storm responders to identify the causes of power outages quicker than in years past. They’ve also established a Lightning Lab research center which tests new equipment that will better withstand lightning’s effects on the power grid. I would be curious to see what ConEd is doing in terms of innovation to better react to New York’s future hurricanes, especially as these advances should help ease the burden of high costs related to emergency response going forward.

[1] “FPL conducts annual storm drill; highlights new technology and emergency response partnerships in advance of 2016 hurricane season,” Electric Energy Online, May 2016, accessed November 2016.

Great post Hugo. As a New Orleans native, I know too well what it’s like to deal with power outages and hurricane damage. The New Orleans-equivalent of NY’s Con Edison, Entergy, is obviously dealing with similar issues related to sustainability and climate change and has been great example in sustainability efforts. The company was the first U.S. utility to voluntarily commit to stabilizing its CO2 emissions, and in 2016 it achieved a grade level A rating (highest possible) from the Global Reporting Initiative.

A large portion of the company’s customer base is located in the Gulf Coast region, which is seeing one of the fastest rates of wetland losses in the world. As it relates to hurricane preparation and preparedness in particular, Entergy has been working with the community to prevent further losses and restore barrier islands and the coastal wetlands. My family, and many others in New Orleans, typically recycle their Christmas trees with Entergy to use for wetland restoration. These wetlands serve as natural protection and barriers to hurricanes in severe weather situations (helping to degrade a storm’s strength by the time it hits the city).

Great post Hugo!

This becomes even more urgent if you consider that at a national level, power outages due to resiliency failures, could be destroying $18-33B in economic value per year (with outliers as high as $75B in 2008) (see report below). The failure to invest in resiliency thus feels like a systemic market failure, ripe for potential government intervention. It is interesting to consider whether a more market driven approach (e.g., regulators taking pressure off of margins with the mandate that additional funds be spent on resiliency) or a government-led approach (e.g., improved set of central standards and approved funding) could be more effective at resolving the market failure. This feels like a problem that would benefit from forced cooperation between the different regional utilities to determine cross-cutting best practices for resiliency measures — I worry that if you left each utility to their own devices a lot of duplicate dollars would be spent developing action plans and inefficient solutions would be implemented. In either case, there is a compelling argument for billions of dollars to be redirected to this problem, potentially substantially more than the $4.5B in recovery funding, which was the last big chunk I was able to identify at the federal level.

http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2013/08/f2/Grid%20Resiliency%20Report_FINAL.pdf

This post reminds of Bernie Sanders’ campaign when he continually harped on the country’s “crumbling infrastructure.” It is remarkable that a storm could knock out power to [one of] the most important cities in the world for over a week. I was living in the East Village during the storm and after lighting my gas stove with a match, cooking eggs I kept on ice, and playing chess for several days, I gave up and migrated north of 23rd street where, by some miracle, there was no sign of an outage. The contrast between both sides of 23rd where the grid changes. It was as if nothing had happened.

I think the interesting point here is how to incentivize change. How do we bring our energy grid in line with the other advancements in the millenium? When government and private industry is so intertwined, this is often difficult to do. I hope the local and federal governments can find ways to subsidize capital investments to spur this much needed growth. As you mention, it is only a matter of time before another storm hits and it will be a complete embarrassment if we are left with the same results.