A Green Merchant of Death?

Long portrayed as a villain, Philip Morris International leads the way on climate change (and gets little credit for it).

As the second-biggest international cigarette company (trailing only China National), and with tobacco use the single-largest preventable cause of death globally, Philip Morris International may indirectly kill more people on earth than any other US-headquartered company.[1] Despite investment in so-called “reduced risk products” like e-cigarettes, the $185B corporate home of The Marlboro Man continues to promote cigarette use worldwide (selling 813 billion cigarettes last year), oftentimes through suspect practices like setting up 10-cent cigarette stands just feet away from Indonesian elementary schools.[2] The company has caught deserved negative media attention – in a 2015 “Last Week Tonight” episode, John Oliver devoted 18 minutes to highlighting PMI’s aggressive overseas promotion of cigarettes.[3] With such negative press, however, a second message is lost: few companies are doing half as much to combat the effects of climate change. From broad-based initiatives to incredibly specific local projects at some of their 48 manufacturing sites around the globe, PMI is paradoxically proving that ‘dirty’ companies with major negative social impacts can, in fact, lead in the way in other important areas.

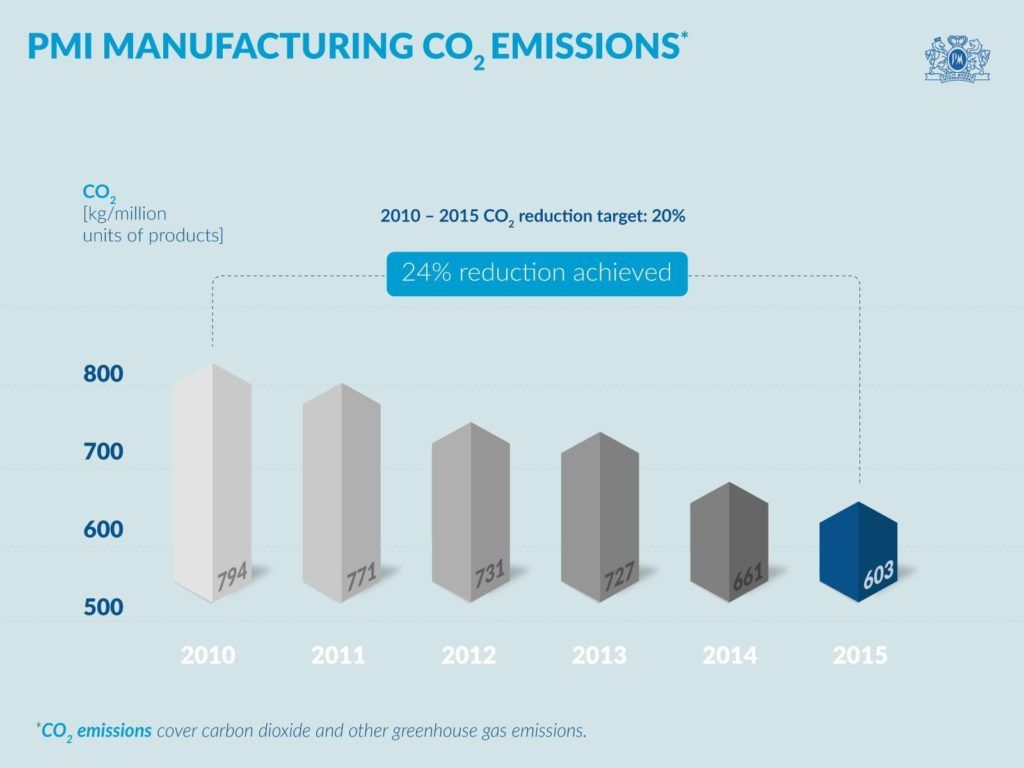

For the past 4 years, Philip Morris International has made The Climate Disclosure Project’s A-List for “comprehensive action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change.”[4] In 2016, PMI was in the top 1% of all companies who submitted data, as it was one out of only 25 companies worldwide to earn two “A” grades– one in climate, one in water (2,500 companies reported data to CDP in 2016).[5] The company has committed to reducing its overall value chain carbon footprint by 30%+ from 2010-2020; as of 2016, it is well ahead of target and has already achieved 27% of the stated 30% reduction; 178 projects have been implemented to date with annual carbon reduction of 64,421 metric tons, while an additional 386 projects worth 97,169 metric tons of carbon underway or planned (see Figure 1 for PMI manufacturing carbon emissions by year, 2010-2015).[6]

Figure 1

Source: https://www.pmi.com/sustainability/pmi-and-the-environment/energy-efficiency-and-carbon-performance

These projects range from the macro (eliminating coal from the curing process globally and procuring green electricity in EU countries) to the micro (e.g., burning rice husks instead of virgin timber in Philippines curing barns).[7] The company’s climate-related goals have science-based targets for measurability, and with the help of Dupont Sustainable Solutions, the company developed its own internal carbon price in 2016 ($17 USD).[8] This price is now used to quantitatively evaluate all proposed projects, making PMI one of the more analytically advanced companies with regard to their climate impact approach.

Why is PMI a climate champion, helping to set the standard for corporate climate change mitigation in the 21st century? A cynical answer would be that this “merchant of death” (per Thank You For Smoking) needs a good message to promote. The positive light from the environmental/climate projects could, in theory, dampen the outcry around a business model premised on supplying deadly, unnecessary products to virtually every country on earth. While PMI certainly is promoting these climate projects, however, the program also simply makes business sense. The company is paying for fewer resources (water, electricity, curing fuel) and workers (79,500 globally) are more productive in healthier operating environments.[9] As a company largely levered to a single crop (tobacco) and with facilities across the globe, PMI is exposed to the effects of the skewed growing seasons and environmental extremes (e.g., drought) associated with climate change.[10] Their resource-dependence mitigation efforts serve to reduce some of these risks posed by a changing climate.

PMI’s actions force us to ask harder questions around which companies are ‘good’ today and how to weigh certain impacts against one another. For example, electric vehicles are often heralded for reducing dependence on fossil fuels, but mining for nickel and cobalt (necessary for lithium ion batteries) results in significant “resource depletion, global warming, ecological toxicity, and human health impacts” (often far from US shores).[11] As with politics, corporate social responsibility (CSR) discourse is too often lacking nuance and acknowledgement of a middle ground. PMI acknowledges climate change, is committed to measurable goals regarding reducing its climate impact, and is a proven leader among large multinational companies in tackling the climate problem head-on. The company should devote more efforts to leading CSR panels, publications, and committees to change the public narrative around the company and spread best practices. They should continue to press on the climate front, proving that organizations can evolve from CSR laggards to leaders, and force a more nuanced debate around what constitutes responsible corporate citizenship. Is setting up kiosks next to schools ever forgivable? No, and PMI should stop these sales tactics. But so long as people in the world are smoking, we’d rather those cigarettes come from PMI’s value chain than anyone else’s. (783 words).

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Fast Facts: Smoking and Tobacco Use.” https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm, accessed November 12, 2017.

[2] Dan Harris and Chris Kilmer, “Is Big Tobacco in US Targeting Youth in Indonesia,” ABC News, ABC, July 10, 2012. http://abcnews.go.com/International/big-tobacco-targeting-youth-indonesia/story?id=16712181, accessed November 12, 2017.

[3] “Tobacco,” Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, HBO, February 15, 2015, hosted by John Oliver. Accessed via HBO GO November 12, 2017.

[4] Philip Morris International, “Climate A-List Company,” https://www.pmi.com/sustainability/pmi-and-the-environment/climate-a-list-company, accessed November 11, 2017.

[5] “Philip Morris International Recognized for Environmental Leadership on CDP’s A List for Climate and Water,” Business Wire, October 24, 2017. http://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/philip-morris-international-recognized-for-environmental-leadership-on-cdp-s-a-list-for-climate-and-water-1005417819 accessed November 12, 2017.

[6] Philip Morris International, “CDP 2017 Climate Change 2017 Information Request,” December 31, 2016: 24. https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/pmi-sustainability/cdp-climate-change-2017-information-request.pdf?sfvrsn=731983b5_2 accessed November 11, 2017.

[7] Ibid: 27.

[8] Chris Martin and Emily Chasan, “Philip Morris Joins Growing Group of Carbon-Pricing Corporations,” Bloomberg News, October 12, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-12/philip-morris-joins-growing-group-of-carbon-pricing-corporations accessed November 13, 2017.

[9] Philip Morris International, “CDP 2017 Climate Change 2017 Information Request,” December 31, 2016: 1. https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/pmi-sustainability/cdp-climate-change-2017-information-request.pdf?sfvrsn=731983b5_2 accessed November 11, 2017.

[10] Henderson, R. M., et al, Climate Change in 2017: Implications for Business (HBS No. 317-032): 8.

[11] United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Application of LifeCycle Assessment to Nanoscale Technology: Lithium-ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles,” April 24, 2013. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-01/documents/lithium_batteries_lca.pdf accessed November 12, 2017.

Very interesting piece – I had no idea PMI is one of the leaders of climate action. It’s surprising that a company would invest so much into making cigarettes more sustainable, when this is likely not a large driver of value for customers. In my opinion, there are two main reasons for the company investing so heavily. First, ensuring the resilience of PMI’s supply chain. PMI will face similar pressures to other agricultural companies in the near future – sourcing crops in climate-resilient locations. By acting on climate now, it will protect its core business, ensuring a constant supply of tobacco in the coming decades. Second, bringing greater legitimacy to its operations. As said in the piece, action on climate will mitigate some of PMI’s negative image.

Philip Morris as a sustainability leader – who would’ve thought? This is an interesting paradox that made me reflect on “moral flexibility” (also per Thank You for Smoking) – I agree that as long as the billion-dollar tobacco industry exists, PMI’s “sustainable cigarettes” are creating value for the environment and customers by offering a “lesser evil”, and they deserve more credit than they are getting.

While this also meets business objectives of cost savings and mitigating environmental variability risks, I wouldn’t undermine the value and CSR motives of these initiatives given PMI has invested in truly market-leading approaches of analytically measuring climate impact and minimizing the value chain’s carbon footprint. They should share these innovations more broadly in the agricultural sector and become a vocal leader in the space, which also serves their brand image well.

On the customer front, smoking has long been seen as a behavior that’s both self-destructive and harmful to others – PMI’s innovation gives them a new point of differentiation to appeal to younger demographics that are more socially aware and responsible (“I care more about the earth than my own body” could be an interesting marketing message). PMI should communicate and market their sustainability efforts more actively to make it a competitive edge.

This is extremely thought-provoking. In today’s world, where access to and spread of information is nearly instantaneous, judgments of a company’s “goodness” or “badness” are often quickly made and deeply held. You raise an important point, which is that this designation is far from black and white. PMI is a great example of this. They have been despicable in their sales tactics, inherently harmful in their impact on customers’ health, and – based on the evidence you’ve provided – a true leader in addressing climate change. I don’t quite know what to make of this, but I must agree that as long as dollars continue to flow into the cigarette industry, I sure hope they’re going to PMI, for the sake of the environment. As the prior comment notes, these are market-leading approaches that can be leveraged across the industry and other agricultural sectors more broadly.

How can we, as consumers, be smart and choiceful about where we put our dollars? I think of the viral responses to one of Uber’s recent scandals: in what appeared to be a misunderstanding, within hours thousands were deleting their Uber app and posting “#deleteuber.” [1] Setting aside the rest of Uber’s tumultuous year… in this isolated scenario customers were quick to conclude that Uber must be “bad” and punish the company by switching to competitors. As the purchasing power of millennials grows, this type of discretion in purchasing behavior will become increasingly important. For companies like PMI, transparency and effective communication will be critical to sway consumers in their favor, giving credit where it’s due.

[1] “What You Need to Know About #DeleteUber”. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/31/business/delete-uber.html

Thank for writing this post! You are absolutely correct about the difficulty of associating PMI with something positive due to the reputation of cigarettes. I had no idea they took fighting Climate Change so seriously. Often in the classroom, we wonder whether a business is taking to benefit the good of mankind, or whether or not they are trying to turn a profit. I see this as a dual-benefit. The fight on Climate Change will clearly impact the world for the better. In the meantime, it potentially mitigates the risk to their supply chain due to climate. As an industry that is dependent on crop growth, they will be one of the first industries impacted.

A particularly interesting topic. I definitely agree with the fact that companies are labeled as “good” or “bad” and that these labels have a greater impact on perception than the actions of the companies themselves. I think photovoltaics is another example of this. Solar companies are often labeled as progressive and environmentally friendly despite the fact that the sourcing and disposal of photovoltaics can have incredibly negative consequences on the environment. Solar companies have a huge range on how ethically they support their materials, but in our haste to leave fossil fuels we often don’t fully understand that some photovoltaics have a net negative effect on the environment (1).

As well, the disposal of photovoltaics have extreme impacts on the environment. It has been found that photovoltaic panels can produce as much as 300x more toxic waste than that from nuclear energy (2). This is due in large part to the metallic compounds used to create photovoltaics. And some companies are taking efforts to recycle photovoltaics and avoid these impacts, but few regulations exist as these companies are often seen as “environmentally friendly.”

How do we bring objectivity to the conversation of the “goodness” of a company? I’m not sure. Bias is an incredibly tricky thing to get rid of. But I think it starts with sitting down, setting universal values, and really looking at data to see what helps and what hurts the most.

(1) https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/energy/2014/11/141111-solar-panel-manufacturing-sustainability-ranking/

(2) http://environmentalprogress.org/big-news/2017/6/21/are-we-headed-for-a-solar-waste-crisis

Thanks for sharing this Nate. You bring up existential points about tackling climate change and the ancillary repercussions of achieving energy sustainability. Solar energy, for example, is a relatively “green” source of energy, but what many critics point to is the process of extracting silicon is determent for the environment in the same way Nickel, Lithium, and Cobalt are for battery storage.

The question is, what is the cost of the move to energy sustainability? the human capital cost involved the millions of jobs at risk in traditional energy sectors as a result of this shit. Another cost is the sunk cost of existing infrastructure and technologies that investors poured in. The third pertinent cost in this case is the fact that the “bad guy” in Phillip Morris is leading the way in energy sustainability as a relative bad actor in it’s long history as a company. The cost, therefore, is relative, and I believe as with any technology, the cost of change in high and will fall off with the long tail

This was a thought-provoking article – I wouldn’t have suspected PMI would have had such best-in-class practices. The negative halo effect on the industry tends to cloak everything it does in a negative light.

I would still argue that the consumer use of its tobacco products is part of PMI’s value chain, and therefore, how PMI designs and broadly influences how consumers use their products could lie under its care. Smoking generates a host of negative externalities – social and air pollution. While I don’t know how much smoking contributes to air pollution, this is definitely something to think about. If we could quantify that and add that to PMI’s carbon emissions number, perhaps we might have to question if the PMI value chain from supplier to consumer really is all that admirable.