Priceline: The Travel Behemoth

The story of how Priceline became the most valuable travel company in the world and the 3rd largest player in all of Internet commerce.

Company Overview

The Priceline Group is the world’s largest online travel company and operates platforms connecting travel suppliers such as hotels with travel buyers. Priceline’s portfolio of businesses includes Booking.com (the leading online travel agency [OTA] in Europe, Latin America, and parts of Asia), Agoda.com (the leading OTA in SE Asia), Kayak (the leading flight meta-search provider), and OpenTable (the leading restaurant reservations website) in addition to its namesake Priceline.com business. In 2015, Priceline is expected to book ~$57 billion of travel expenditures and will capture ~$8.5 billion, or ~15% of the spend, as gross profit.

Building a Network Effect Business

Since a near-death experience with the burst of the dot-com bubble, Priceline has become one of the world’s most important internet companies. In fact, Priceline is the 3rd largest e-commerce company in the world (by gross merchandise value) after Alibaba and Amazon and its flagship property, Booking.com, is the 3rd most global website in the world (based on the number of countries in which its used and user traffic in each country) after Google and Facebook.

The secret to Priceline’s revival lies in its 2005 acquisition of Booking.com for $135 million. The property now accounts for >80% of Priceline’s market value of $65 billion (per Wall Street research) and is widely acknowledged to be the most successful acquisition in internet history. Booking.com was among the first online travel companies to capitalize on indirect network effects. It realized that travel suppliers prefer to sell their inventory through channels with the most users and that users prefer to buy through channels with the greatest supply. As a result, there are meaningful demand-side benefits to scale.

To build scale, Booking.com initially focused on providing the most valuable standalone solution to both sides of its platform. Booking.com employed the following strategies to add suppliers:

- Booking.com was the first to deploy a salesforce to service the long tail of travel suppliers (i.e. independent hotels) and add them to its platform. It therefore had the “first-mover advantage” with many suppliers.

- Booking.com realized that it would add greatest value to (and extract greatest value from) travel suppliers in the most fragmented markets due to simple competitive forces – greater supplier fragmentation reduces supplier power. Practically, this meant focusing on hotel suppliers instead of airlines because airlines had sufficient scale to drive traffic to their own websites / call centers. Priceline/Booking’s business today is ~87% hotel. It also meant focusing on international markets instead of the US. In the US, 2/3 of hotel properties are affiliated with chains who offer them bargaining power. The comparable figure is 1/3 in Europe and an even smaller proportion in other geographies. Priceline’s mix of business today is 87% international.

- Booking.com offered hotels the most attractive payment model and payment terms. Expedia and Travelocity focused on the “merchant” model whereby they took payment from consumers at reservation and kept 25% before remitting the remainder to hoteliers at the time of stay. Booking.com used the “agency” model whereby the hotel remained the merchant of record and Booking.com simply took a 15% commission. Booking.com’s model was both cheaper and more efficient for hoteliers (http://skift.com/2012/06/25/how-booking-com-conquered-world/).

- It was not easy for smaller, unsophisticated travel suppliers to connect to OTAs because it was challenging to manage inventory offered through multiple websites in addition to more traditional channels (i.e. phone reservations, walk-ins, etc.). Booking.com therefore offered them an efficient technology interface to help connect with its platform (http://www.tnooz.com/article/why-pricelines-purchase-of-booking-com-was-the-most-profitable-travel-deal-of-the-2000s/). The difficulty of connecting to other platforms mitigated the threat of multi-homing among hotel suppliers.

Booking.com also deployed multiple strategies to maximize users:

- It offered high-touch customer service to ensure user satisfaction.

- It spent liberally on online advertising to drive consumer traffic to its website in the hope that it could not only convert them for the first transaction, but that it could convince users to visit Booking.com directly for future transactions. In fact, today, the Priceline Group is among the world’s largest purchasers of online advertising and is Google’s single biggest customer (http://skift.com/2014/05/21/priceline-and-expedia-are-googles-two-most-important-advertisers/).

- Booking.com and Priceline more generally developed a competency in data analytics. It optimized its websites to provide the most relevant results from search queries and to maximize conversion with the most seamless user experience. This increased Priceline’s “quality score” within Google’s search algorithm and improved placement of Priceline’s sites in response to search queries. This creates a direct network effect – the more users that Priceline can attract, the more data it has to optimize its website to improve its quality / maximize conversion; the more it can improve quality/conversion, the higher its sites will be rated and the easier it will be to attract users (http://www.barrons.com/articles/priceline-stock-dominant-growing-and-undervalued-1433457842). In some ways, this is similar to the network effect that Google itself experiences whereby scale improves the quality of its search results. This “direct” network effect has the effect of increasing user traffic/conversion, which in turn drives and protects the aforementioned “indirect” network effect between users and travel suppliers.

The Impact of a Network Effect

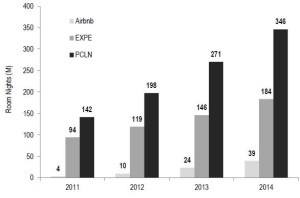

Priceline / Booking.com’s strategy to develop strong network effects succeeded and the results are stunning. Priceline’s room-nights booked are larger and faster-growing than Expedia and are much larger than the upstart Airbnb:

Source: comScore, Wall Street analyst research

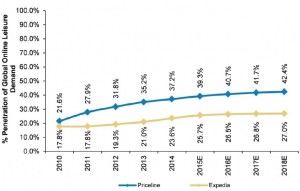

Priceline accounts for ~40% of all online leisure travel bookings vs. 26% for Expedia, its closest competitor (the share figures are even higher when viewed just as a % of OTA booking rather than all online). Priceline’s share gains have healthily outpaced Expedia’s:

Source: Morgan Stanley Research

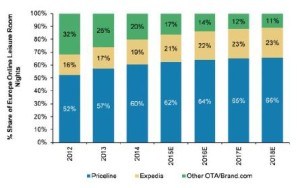

The market share figures are even more amazing in Priceline’s strongest market, Europe, where Priceline processes 60% of all online leisure travel bookings:

Source: Phocuswright, Morgan Stanley research

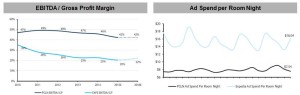

Not only has Priceline achieved greater scale and faster growth vs. Expedia, but it has done so with far lower customer acquisition costs and far higher profitability:

Source: Barclays Research

Protect the Network Effect

Given how successful Priceline has been, it has attracted meaningful competition that is attempting to weaken its network effects and take some of its profit pie. Below is a sampling of competitive threats:

- Software vendors like Sabre and TravelClick have developed SaaS technology for independent hotels to more easily manage their properties and reservations. This has enabled them hotels to more easily connect with multiple bookings websites. The increased ease of “multi-homing” has weakened Priceline’s indirect network effects.

- Players further up the “travel funnel” are attempting to break Priceline’s network effect by changing consumer behavior. For instance, many travelers look at hotel reviews on TripAdvisor prior to booking their stay on Priceline. TripAdvisor has launched an initiative called Instant Booking whereby it is adding hotel inventory so that consumers can more easily book their stay after looking at reviews rather than going to another site like Priceline.

- Independent hotels are taking advantage of website building tools to develop their own online presence. As such, these hotels are trying to drive more traffic directly to their sites so that they don’t have to pay a commission to Priceline or another OTA. Consumers are increasingly comfortable booking directly due to the availability of online reviews.

- New-age players like AirBnB are trying to disrupt the entire model of accommodations. Insofar as AirBnB succeeds in driving travelers away from traditional hotels, this could make Priceline’s vast hotel supplier network less relevant.

It remains to be seen whether Priceline can stave off these threats, but between the increased ease of multi-homing and more direct competition from complementers (like TripAdvisor) and suppliers (the hotels themselves), it seems clear that Priceline’s network effects going forward will not be as strong as they were in prior years.